Heinrich Christian Gottfried von Struve (born January 10, 1772 in Regensburg, † January 9, 1851 in Hamburg) was a German diplomat and mineralogist. Heinrich was the son of the Russian agent and later Russian ambassador in Regensburg Anton Sebastian and Sophia Dorothea (Reimers) von Struve. Heinrich’s older brothers Johann Christoph Gustav von Struve and Johann Georg von Struve also became diplomats.

He married Elisabeth Wilhelmine Sidonie von Oexle Friedenberg (1780 – 1837) and they had two children:

- Gustav Anton Caspar August (1801 – 1865) who married Alexandrina von Stenbock (von der Osten-Driesen)

- Therese Henriette Antoinette Elisabeth (1804 – 1852) who married 1) Robert Gabriel von Bacheracht and 2) Heinrich von Lützow.

Struve attended high school in his hometown, studied political science in Erlangen and came to Bonn around the beginning of 1789, presumably to visit his sister Susanna Maria († March 1789 in Bonn) who was married to the diplomat Johann Ludwig Dörfeld (1744 –1829). Heinrich for some reason decided to stay in this city and complete his education at the local university. It was probably there that he also met Beethoven, who enrolled in 1789 as a student at the University of Bonn (at the Faculty of Philosophy). Although Struve was unlikely to have had much opportunity to attend classes due to his many official and family responsibilities (he had two younger brothers and a drunken father in his arms), the very atmosphere of the University of Bonn had a very strong and beneficial influence on him.

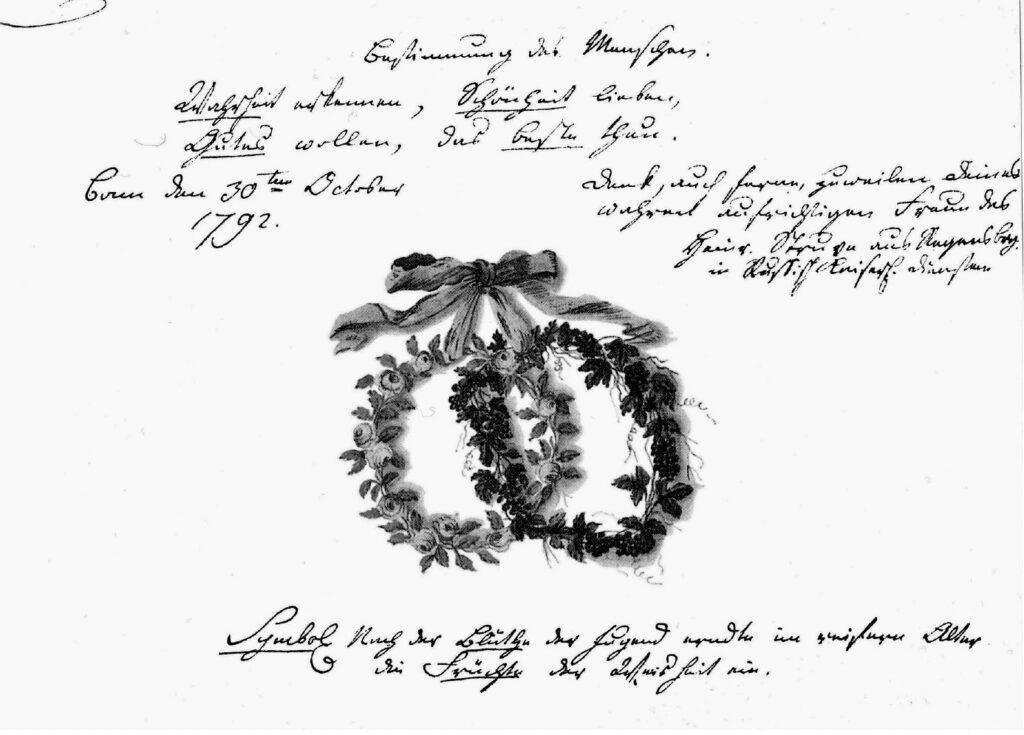

Struve stayed in Bonn even after the death of his sister, and was soon one of the young Beethoven’s closest friends. On October 30, 1792, Struve wrote a few lines (below) in the composer’s record book [Stammbuch], which the composer received as a gift in November of 1792, before his departure from Bonn to Vienna, where he would reside until his death:

Destiny of man.

Recognize truth, love beauty,

Wanting good, doing the best.

Think distant too, sometimes yours

true sincere friend

the fruits of wisdom.

Heinr. Struve from Regensbrg in Russian Kaiserl. Services, Bonn, October 30th, 1792

In the first three lines Struve quotes the Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn. His signature indicates that he was already in the Russian civil service at the time – presumably as an assistant to his father. When Beethoven moved from Boon to Vienna, Struve accompanied him on the journey.

This brief note is followed by an illustration by Struve of two entwined wreaths: one wound with roses, the other with ripe grapes, representing the blossoms of youth, and the fruit of wisdom in “ripe, old age.” Struve borrowed the first two verses from Mendelssohn’s entry in the Stammbuch of Norwegian artist Jacob Peter Hersleb.

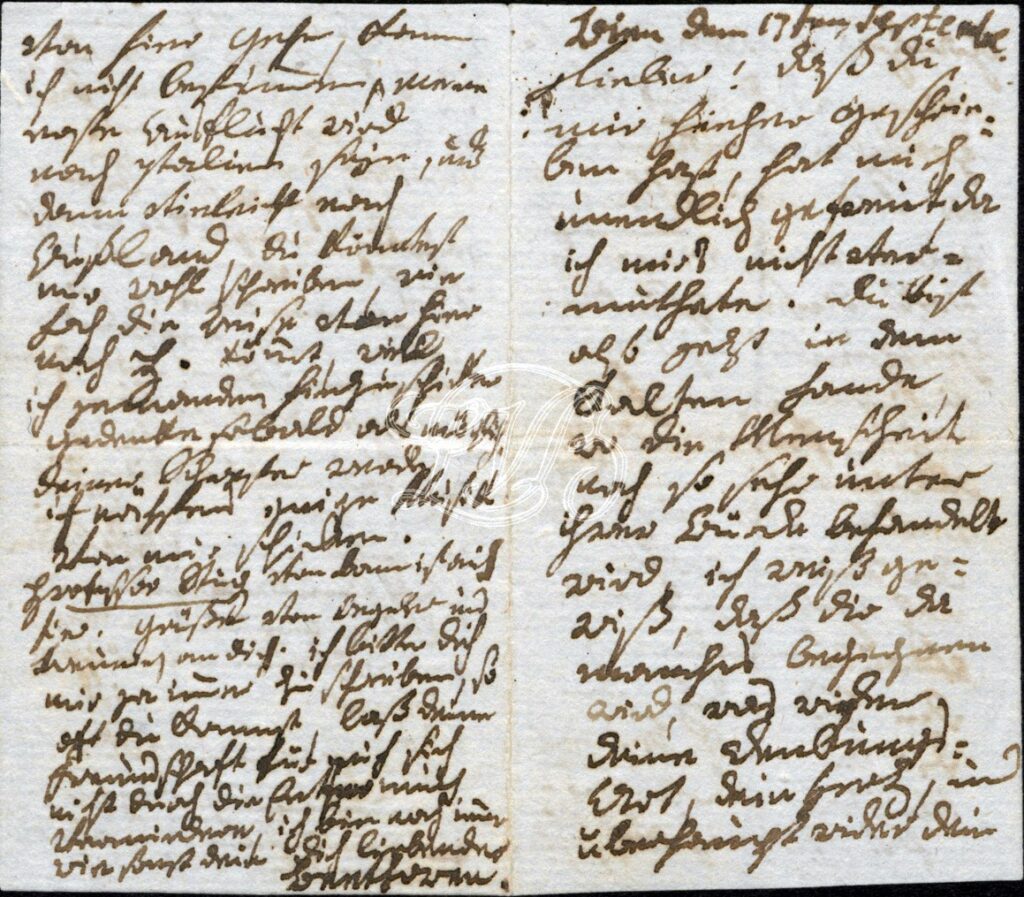

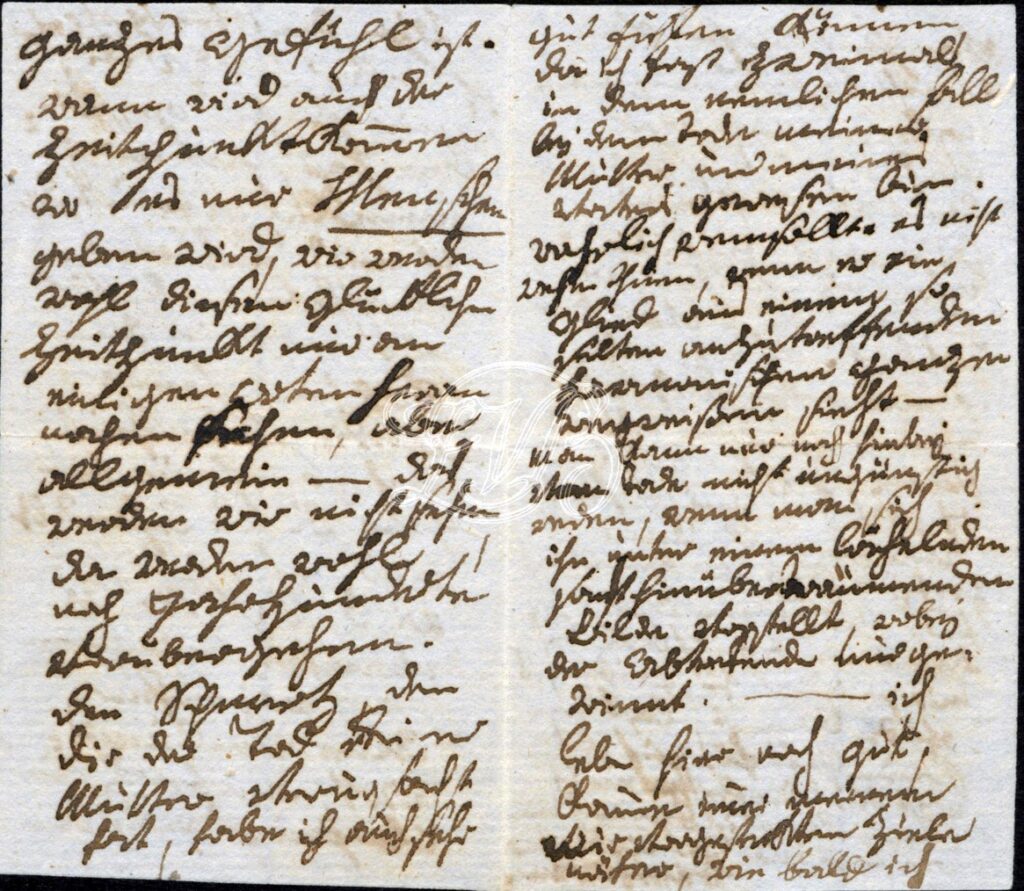

Below, a letter to Heinrich from Ludwig van Beethoven, Vienna, September 17, 1795.

In the letter, Beethoven expresses pity for his friend who had travelled to Russia as Struve had to stay in a cold country where humankind was treated in such an undignified way. From their time together in Bonn, Beethoven knows that these conditions are in contrast to Struve’s set of mind, beliefs and conviction. Beethoven wonders when there will be a time when there are only civilized human beings. However, he doubts whether such a “serene moment” will soon come true in any place on earth. Instead, he believes, it will take several centuries to come. Beethoven also expresses his condolences to Struve on the death of Struve’s mother and utters some thoughts about death in general. Furthermore, he is mentions plans to travel to Italy and Russia. Finally, he extends to Struve his best wishes and also to Struve from their common Bonn friends Franz Gerhard Wegeler and Lorenz von Breuning who are staying in Vienna at that moment as well. While living in Vienna, Beethoven repeatedly complained that it was impossible to find true friends in the imperial capital, such as he had in Bonn.

In 1796, Struve became the secretary of his illustrious compatriot, a native of Regensburg, writer, journalist and diplomat, Baron Friedrich Melchior von Grimm (1723–1807), whom Catherine II appointed as the Russian envoy in Hamburg. After the death of the empress (November 6/17, 1796), her heir Paul I confirmed this honorable, but burdensome appointment for the elderly diplomat. So Struve, together with his patron, ended up in Hamburg, a city with which he was later associated for many years, although he also worked in other Russian embassies and missions (in Stuttgart and Kassel). In 1815-1820 he was Chargé d’Affaires in Hamburg, in 1820-1843 – Minister-Resident, in 1843-1855 – Ambassador Extraordinary, after which he resigned. By that time, he had long since started a family, having married in 1801 the Countess Elisabeth Wilhelmina von Axle-Friedeberg (she died in 1837). For these reasons, the personal archive of Heinrich Struve remained in Hamburg, where the letter from Beethoven was discovered.

In 1810 he was elected a corresponding member of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences. From 1813 Struve was appointed Russian Chargé d’Affaires, then Minister Resident and from 1821 Russian State Council in the Hanseatic cities of Bremen, Hamburg and Lübeck. In recognition of his services, he was awarded the Order of St. Anne second class in 1812 and the Order of St. Vladimir in 1814. In 1816 he became a corresponding member of the Imperial Russian Academy of Sciences. [5]

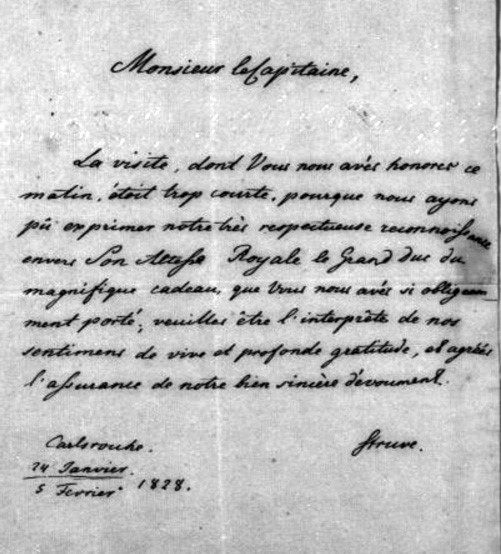

Below, Struve’s letter to Heinrich von Hennenhofer – thanking him for an audience with Grand Duke Ludwig:

Not all of Struve’s diplomatic efforts were met with success. For a number of reasons, the Russian mission to China which was intended to sort out Russia-Chinese border issues was not crowned with success and was not even completed: the delegation only reached Mongolia and returned back. Apparently, the Russians refused to kowtow to Chinese court ritual and conventions, so after three months of haggling the Russians left. Struve returned to St. Petersburg on December 18, 1806. Sometime after his return, on February 28, 1807, he published an article in No. 22 of the St. Petersburg newspaper, in which he described the actual failure of this mission. A similar article titled “Geographical Ephemeris” then appeared in one of the Berlin newspapers, and the suspicion of disclosing such information about the embassy fell on Struve.

In addition to his diplomatic work, Struve was a passionate and knowledgeable mineral collector. He wrote several specialist books on mineralogy. His collection was acquired by the Natural Science Association in Bremen in 1820, the majority of which are now held by the University of Bremen. In the address books of Hamburg for the years 1830 and later there are repeated references to “the great valuable and, due to the excellent systematic arrangement and selection of the specimens, extremely instructive mineral collection”. Other parts of Struve’s collection are preserved in the Mineralogical Museum of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow. Struve was co-founder of a natural science museum in Hamburg and was made an honorary citizen of Hamburg on August 10, 1843 on the occasion of his 50th anniversary of service. In 1822 he was elected a member of the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina. He was also the first president of the Natural Science Association in Hamburg.

In Hamburg he was a member of the Masonic Lodge Absalom zu den Three Netteln.

Struve’s passion for mineralogy was far more than a hobby. He soon enjoyed a national reputation in this field. The chemist Georg Ludwig Ulex named the mineral struvite after Struve. (A phosphate mineral. First described from medieval sewer systems in Hamburg Germany in 1845). In Hamburg, too, early thought was given to appreciating Struve, who was committed to trade and science. From autumn 1840 the considerations became more concrete. The 50th anniversary of Struve’s service in the summer of 1843 then served as a welcome occasion for the granting of honorary citizenship.

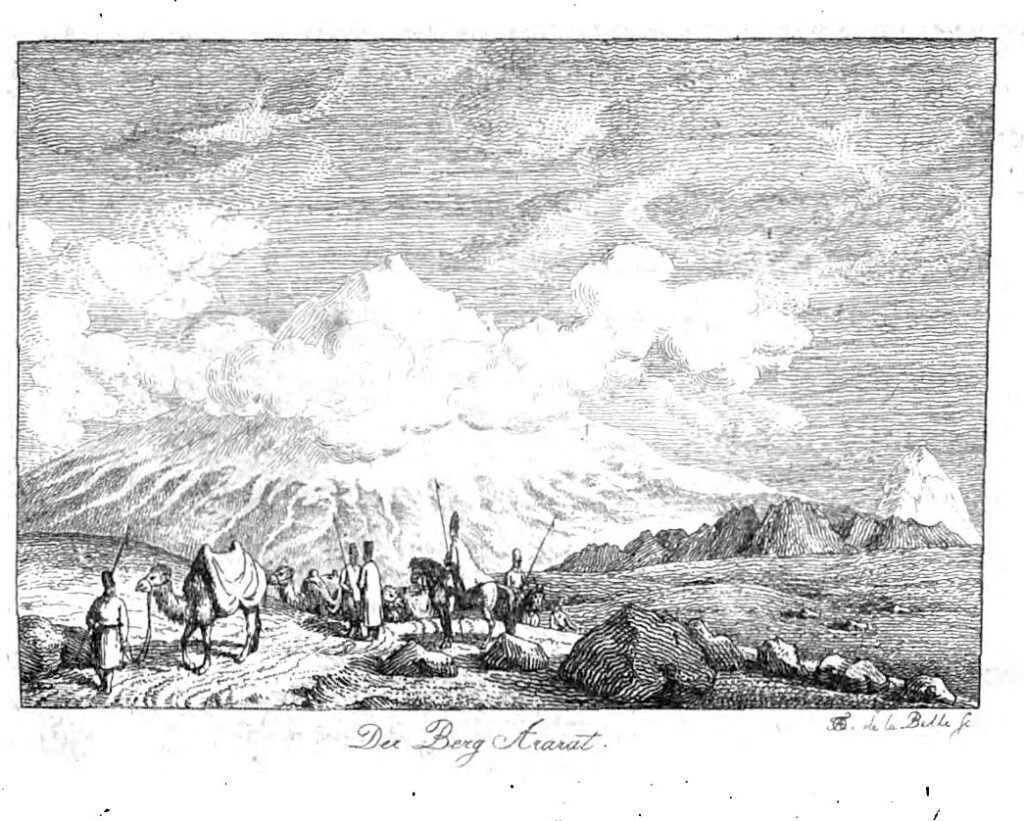

With Frederika Kudriavskaia von Freygang and Wilhelm von Freygang: Briefe über den Kaukasus und Georgien (Letters about the Caucasus and Georgia) from 1812. Strauss, Vienna 1826 (below).

Below, Heinrich von Struve’s Contributions to the mineralogy and geology of northern America. Adapted from American magazines.