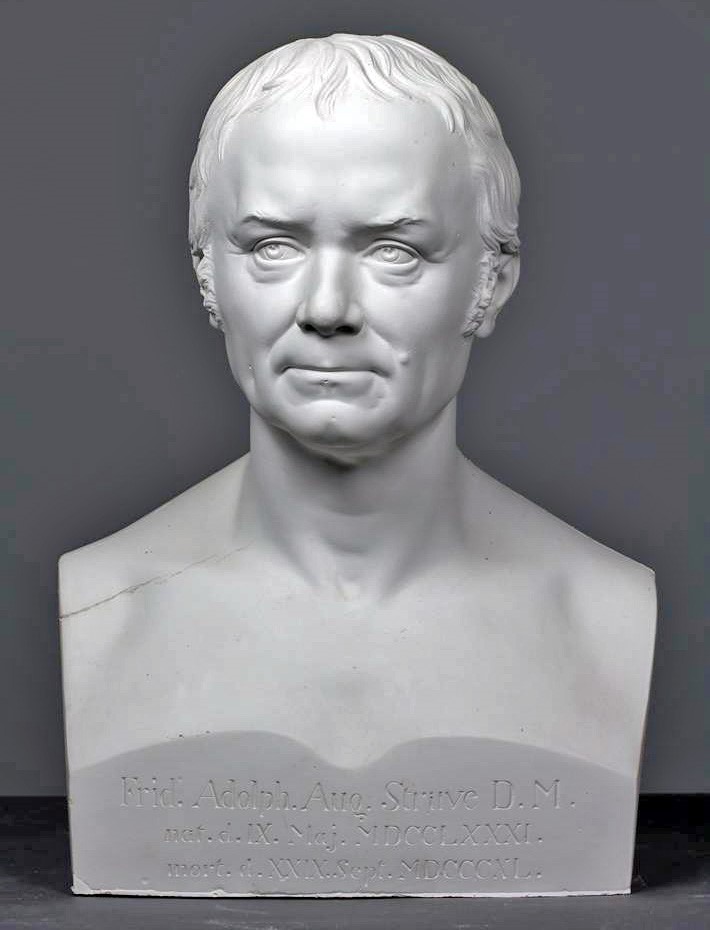

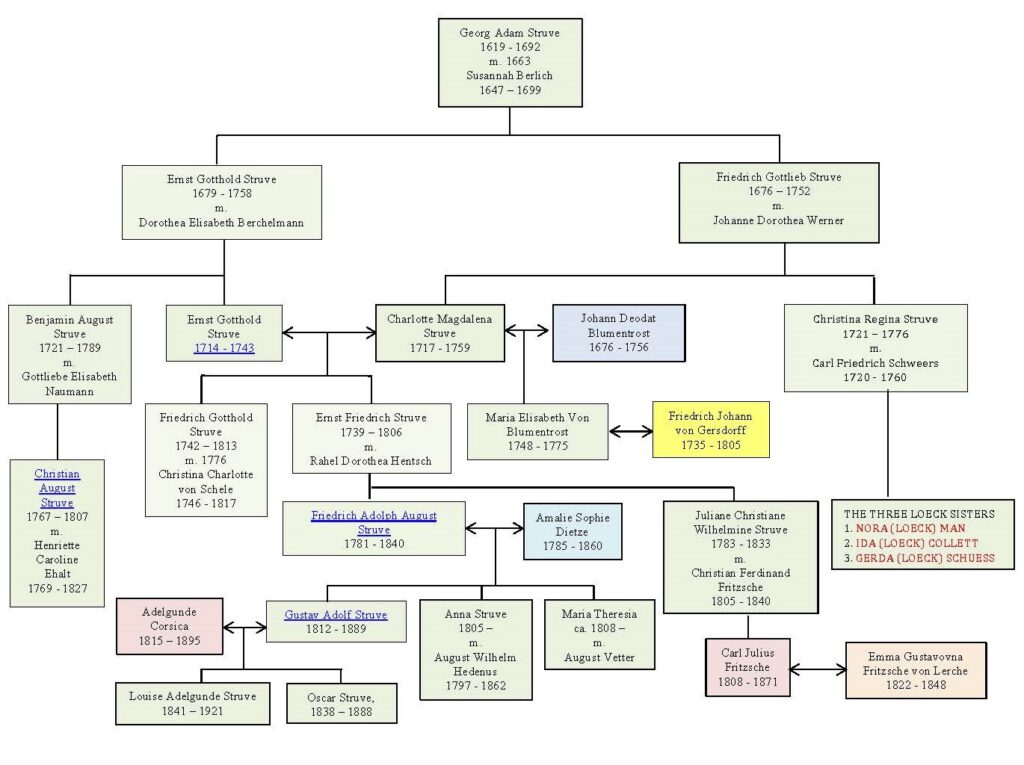

Friedrich Adolf / Adolph August Struve (1781 – 1840) was the son of Ernst Friedrich Struve and Rahel Dorothea Hentsch. He married twice: i) Karoline Friederike Bredemann and ii) Amalie Sophie Dietze. They had the following children:

- Anna Struve (1805 – ) who married August Wilhelm Hedenus

- Maria Theresia (ca. 1808 – ) who married August Vetter

- Gustav Adolf Struve (1812 – 1889) who married Johanna Adelgunde Corsica (see the end of this page)

His sister, Juliane Christiane Wilhelmine Struve, married Christian Ferdinand Fritzsche

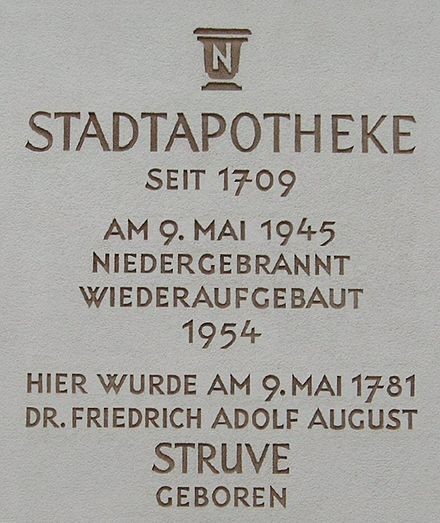

His origins are to be found in the area of Neustadt, Saxony. After attending the Princely School in Meißen, Friedrich studied medicine in Leipzig and Halle. In 1803 he settled in Stolpen as a doctor and pharmacist. Two years later, by marriage to Amalia Dietze, Struve came into the possession of the Dresden Salomonis pharmacy on Neumarkt. Here he began, stimulated by his own experience of a poisoning illness, which he contracted during experiments with hydrogen cyanide, to deal with the production of artificial mineral water. The sparkling initial idea came to him during his healing cures in the Bohemian Karlsbad and Marienbad.

The aim of his curious research: a scientifically exact replica of natural mineral-containing water with exact determination of the source components (including magnesium, sodium, potassium, calcium, zinc, iodide, and fluoride). Even the smell and taste of the water should be mimicked. A brilliant business idea!

Theodor Fontane later wrote in his book: From Twenty to Thirty about Friedrich Adolf Struve: “Struve is considered the absolute number one in Germany, I would almost like to say in the whole world …”.

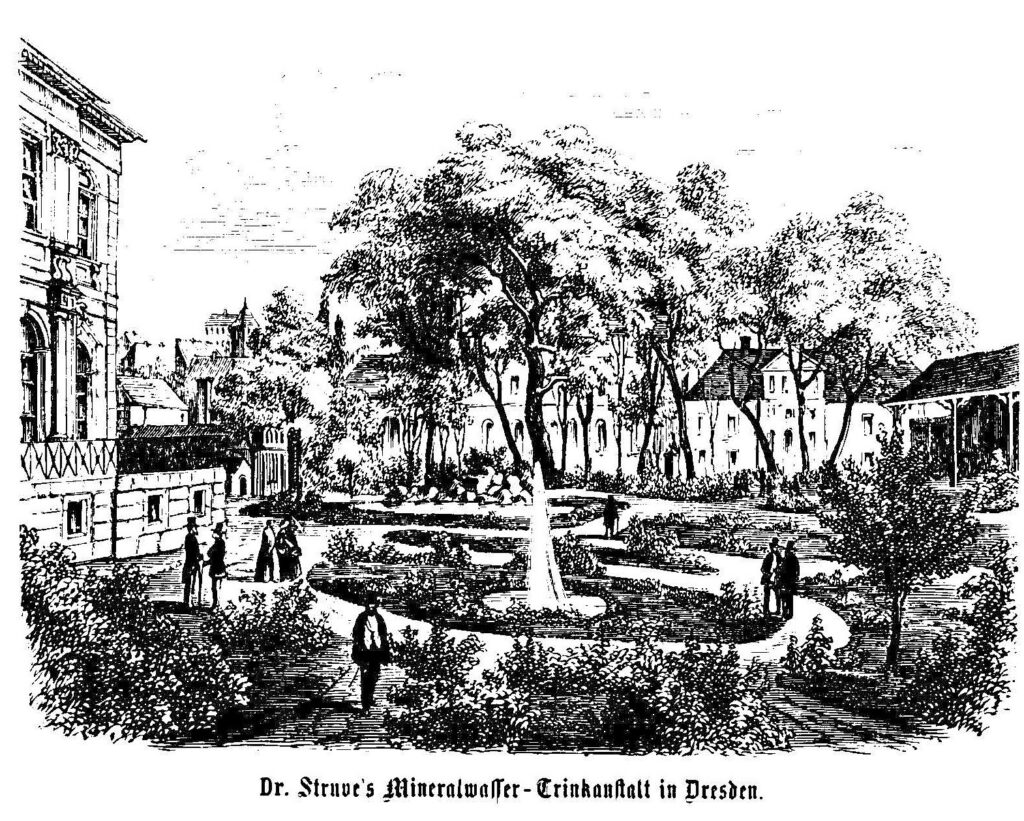

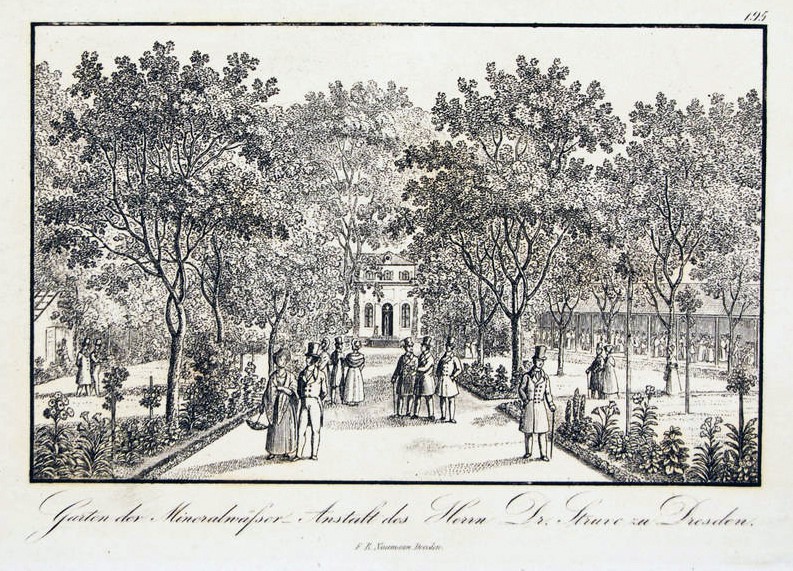

For his tireless work in the field of medicinal drinking establishments, such as the establishment of his “Royal Saxon concessioned mineral water establishment” in 1820, Struve received the Order of Merit from the Saxon King. Even a street was named after him. The Saxon state knew how to appreciate flexible entrepreneurship and innovations.

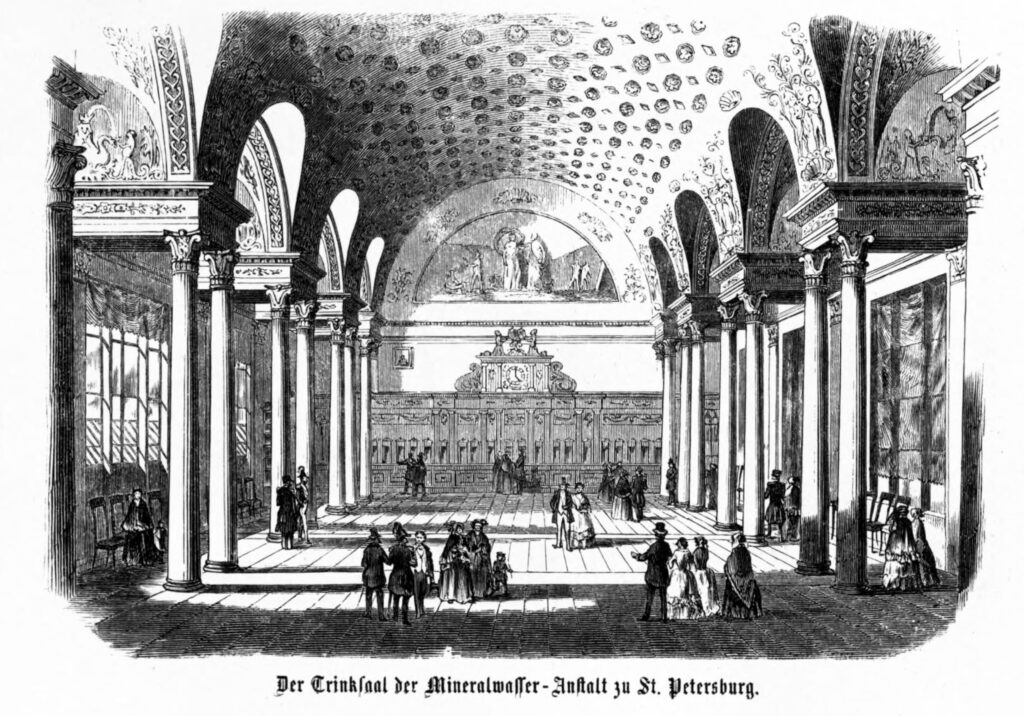

His idea soon caught on all over Europe. Under Struve’s influence and in some cases direction, mineral water institutions and spas were established in Hanover, Leipzig, Warsaw, Brighton, Koenigsberg (today Kaliningrad), St Petersburg, Kiev, Moscow, and many other cities in Europe, which were run by his students. Below, two examples of Struve’s bottled mineral water: “The mineral waters about which you were asking are all made here by Dr. Struve in whose garden they are to be had, and where you can go through any prescribed course of drinking without the trouble of going to the watering place!”

Struve was also a great tinkerer, according to Wilhelm Kügelgen “with attempts to make sugar from potatoes to replace the increasingly expensive cane sugar.”

Below Extracted From: The Royal German Spa:

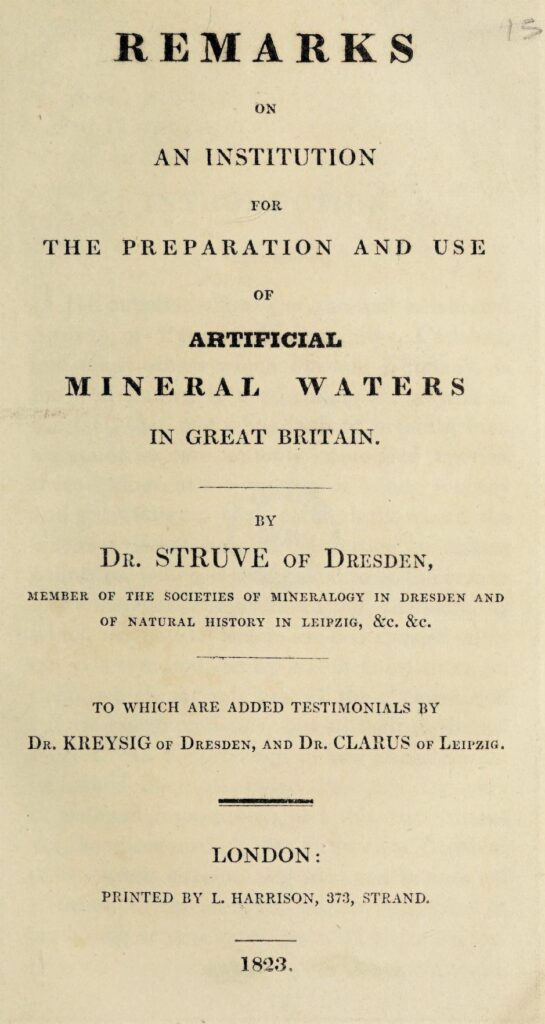

Whilst the manufacture of mineral waters was carried on in Paris and other French towns and these products were widely used both by the public and by physicians in France, one of the most successful of all such ventures emanated from Dresden in Germany in the 1820s. Friedrich Struve, a Dresden physician, became interested in the properties of certain German mineral waters about 1818. After analyzing some of these waters, Struve, went on to devise methods of imitating them for his own use. He regarded all the constituents of these waters as essential, including those which were otherwise thought harmful and those which were present only in minute amounts. He found his artificial mixtures so effective that he invited medical colleagues and friends to sample them and they became so popular that he quickly found himself in an expanding business. He secured favourable testimonials from two eminent Dresden physicians and boldly claimed that his artificial mineral waters were exact imitations of the natural ones. They contained, he said:

‘… all the qualities and properties, in the most minute degree, of their corresponding natural springs, as well in the effect produced on the human body in its most refined distinctions, as in their chemical analysis, taste, intensity of union and the manner of their decomposition when exposed to the air . . .’

Within a few years Struve had opened centres supplying artificial copies of Carlsbad, Ems, Marienbad, Pyrmont, Spa, Seidschutz and Pullna waters in several European towns including Brighton. In his prospectus Struve gave his analyses of eleven different German mineral waters to be supplied at Brighton along with copies of the waters of Vichy in France and Saratoga Springs in America. These analyses were continually revised and improved, especially by Edward Schweitzer, Struve’s scientific director at Brighton.

The German Spa at Brighton was highly regarded by many well-known physicians, not least A. B. Granville who began to use these artificial mineral waters in his fashionable London practice from about 1826. On his journey across Europe to St. Petersburg in 1828 he met Struve in Dresden and having formed a good opinion of his professional work, recommended his artificial mineral waters equally with the natural ones. Granville helped to bring Struve into notice in this Country through his popular accounts of the Spas, first of Germany and later of England, in both of which he praised Struve’s preparations. The only reservation he expressed about the fact that so many different waters could be obtained in one place was that patients often drank a random mixture of them, sometimes even under medical advice; Granville thought this would do more harm than good.

In 1836 Charles Daubeny, professor of Chemistry and Botany at Oxford commented favourably on Struve’s establishments and methods in: a A Report on Mineral and Thermal Waters to the British Association. Daubeny was particularly impressed by the emphasis Struve placed on including all the ingredients in his artificial mixtures.

‘… and no one principle omitted, however small may be its quantity in nature, or however inert it may in itself be, it being recollected that the introduction of a fresh substance, by the affinities it exerts, alters, according to the Berzelian doctrine, the proportions of all the salts previously existing in the water … When thus prepared, the facitious water will coincide with the natural one in taste, smell, specific gravity, and other physical properties. The gas bubbles will rise in the same form, and spontaneous decomposition will take place within the same period and to the same extent.’

Daubeny said that he thought Struve’s mineral waters largely fulfilled these conditions. He noted that they were made by methods which prevented the access of air and maintained constant pressure and temperature; he also remarked that they had stood the test of rigorous chemical analysis. Like Granville, he considered that these· artificial mineral waters resembled the natural waters quite closely.

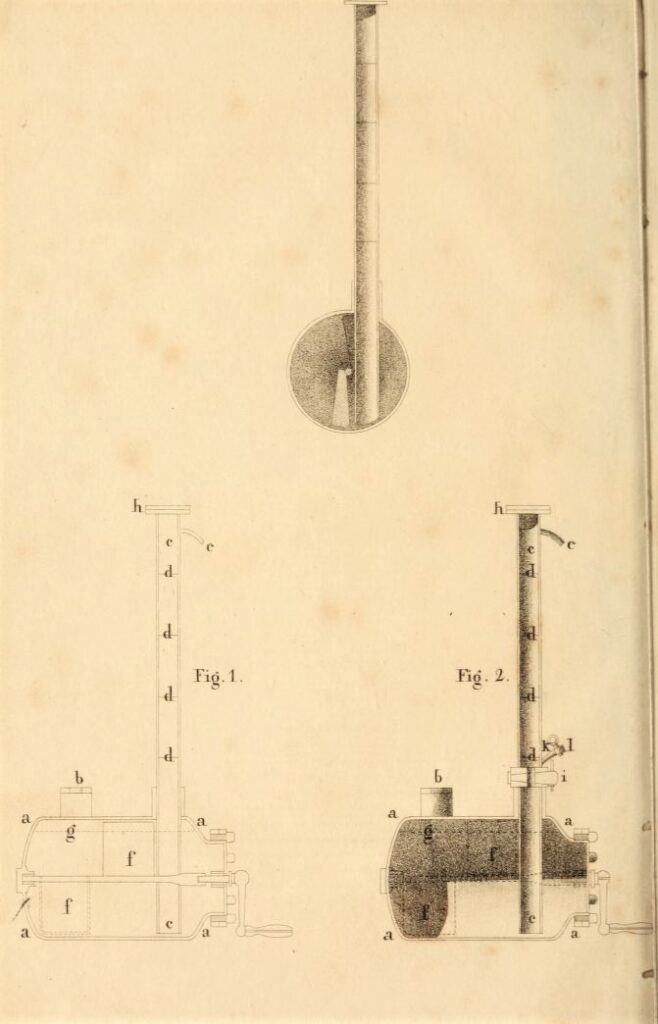

Struve’s establishments were organized in two distinct departments, the laboratory and the dispensary. In the former the carbon dioxide and the various salts and minerals were prepared and purified, the spring water was distilled, and the compound mixtures made up. The dispensing department contained the complicated apparatus in which the mineral waters were aerated and kept under constant pressures and temperatures appropriate to each mixture. The design of the apparatus, which was the subject of patents, remained a well-kept secret, although]. H. A. Franz gave some details of Struve’s methods as did Edwin Lee, a Brighton physician who wrote widely on mineral waters.

Interestingly, Lee summarized what he saw as the main arguments.

“against the similarity of artificial and natural mineral waters. In the first place, since new elements are frequently detected in mineral springs as chemical analysis improves, Lee said, it could not be claimed that the artificial waters exactly resemble their natural counterparts. The latter are more intimately mixed and their heat, being of volcanic origin, has more profound effects on the body than artificially produced heat, he said. Furthermore, natural mineral waters often contain an animal substance not discoverable by chemical analysis and mineral springs, especially thermal ones, have a ‘living property’ and frequently produce effects on the animal system which cannot be accounted for by their chemical components alone. Thus, even in the mid-nineteenth century the arguments of vitalism could still be advanced in efforts to, preserve the mystique of mineral water treatments.

Nevertheless, the chief advantages of Struve’s work for the medical profession came from the detailed analyses of the waters he supplied and the possibilities he provided of comparing the medicinal effects of mineral waters from widely separated sources. The close resemblance in medicinal properties between well-prepared artificial mineral waters and their natural counterparts was frequently noted by physicians, especially those concerned with the treatment of. urinary diseases.

William Prout, whose work in this field was well-known, recommended Vichy water which is mildly alkaline, as a possible solvent for small stones and gravel, although he warned his patients not to expect too much from the use of mineral waters even over long periods of treatment. He thought that the artificial mineral waters, ‘when duly prepared and adjusted to particular cases … ‘ were medicinally as efficient as the natural ones and the principal differences between them arose, not from the composition of the artificial waters, but from the absence of those concomitant factors of a fresh environment, diet, exercise and friendships which accompany the visit to a Spa in its season.

Golding Bird, the fashionable London physician, also prescribed Vichy water in the treatment of uric acid gravel, but for those who were unable to travel to the Spa to obtain the natural mineral water he recommended Struve’s product, for, ‘The artificial Vichy water prepared at the German Spa at Brighton, and which may be procured in pint bottles, possesses all the value of the natural water. Indeed, I think, it is preferrable from its purity, and from its being more highly charged with carbonic acid … ‘

The German Spa was patronized by George IV who gave it the right to use the word ‘Royal’ in its title and to display the Royal Arms. William IV in 1835 granted the Spa the Royal Warrant, a privilege successively granted by Queen Victoria, Edward VII and George V. Struve died in 1840 and the pump room at Brighton closed soon afterwards, although the manufacture of mineral waters both there and in London continued to flourish, gradually developing into the production of sweetened and fruit flavoured ‘soft drinks’ .

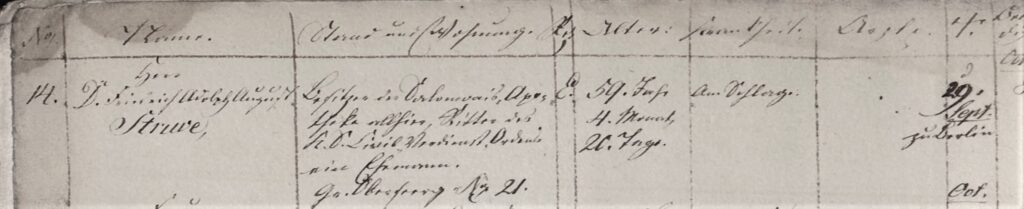

Below, Struve’s burial record:

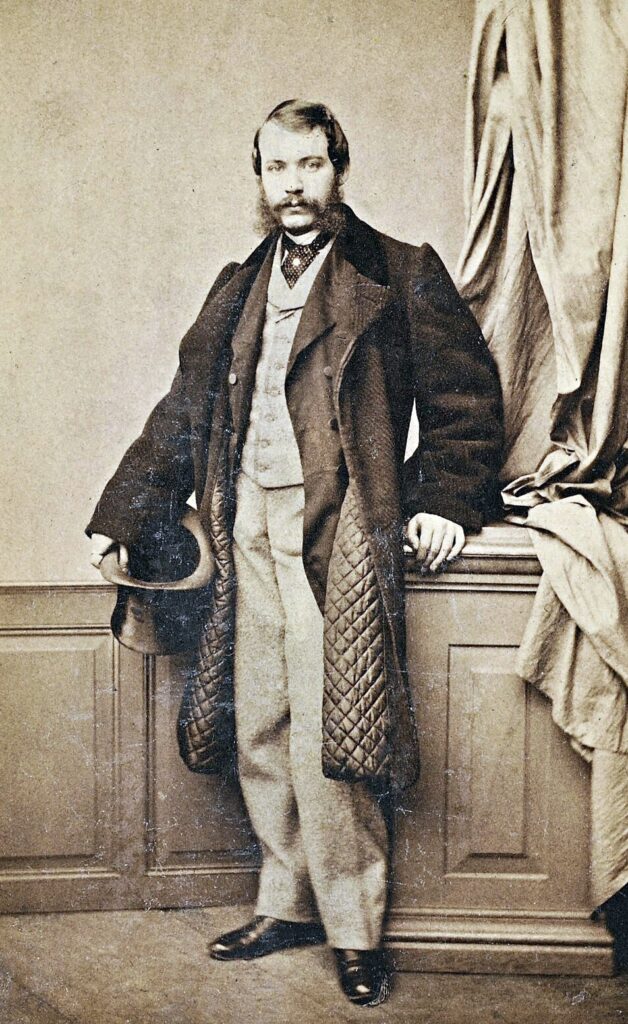

GUSTAV ADOLPH STRUVE 1812 – 1899

Gustav Adolph Struve was the son of the above, he married Adelgunde Corsica (1815 – 1895).

They had one daughter – Louise Adelgunde Struve (1841 – 1921). Louise married a Bremen businessman Carl Theordor Melchers (1839 – 1923) in 1864. And a son Oscar Gustav Adolph (1838 – 1888).

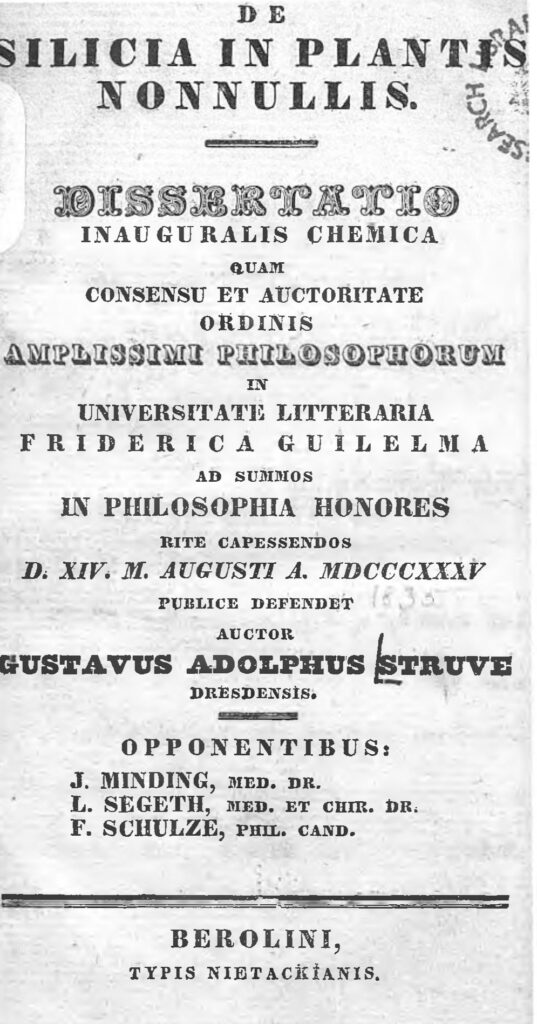

Gustav Adolph attended the University of Berlin and the title of his doctorate was: De silicia in plantis nonnullis … 1835.

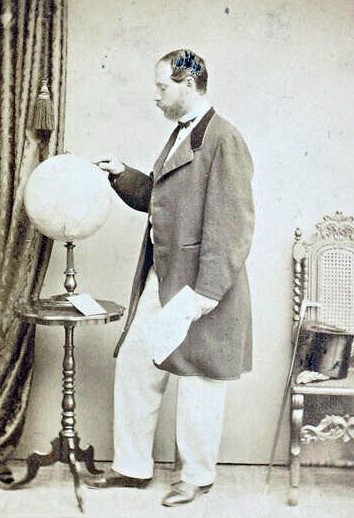

Gustav Adolph built on his father’s success and began producing bottled mineral water on a vacant property in a southern suburb of Dresden near the lake. Later in 1852, due to the huge profit generated by mineral water production, he had the architect Nicolai build one of the most well-proportioned Dresden villas on the brand new Prager Strasse (destroyed in 1945), according to Volker Helas it was “the most important villa building of the 19th century after Semper’s Villa Rosa”.

Its spacious health gardens delighted the post-revolutionary Biedermeier Dresden public, including winding paths, and that super-selling hit, the non-alcoholic and health-promoting refreshment drink -: mineral water.

Many Europeans came to Struve’s Dresden spa and an English-language city map of Dresden of the time marked the sanatorium as the “Water Manufactory”. In the summer season, between 500 and 600 spa guests are said to have frequented the facility with “steam baths and showers”.

OSCAR STRUVE Dr. phil. Oscar Gustav Adolph Struve, (born July 5, 1838 in Dresden, † November 28, 1888 in Leipzig) son of the above; was a German chemist and entrepreneur. He was from 1862 part and no later than 1886 sole owner of the table water factory, which his grandfather Friedrich August Struve (1781-1840) had founded and which he took over from his father Gustav Adolph Struve (1812-1889).

Oscar Struve attended grammar school in Dresden and, after passing his school leaving examination, began studying “chemical engineering” at the Dresden Polytechnic in 1856, which he successfully completed in 1860. After studying in Dresden, Struve went to Leipzig.

After Oscar’s father Gustav Adolph Struve opened a branch of his “Royal Saxon Concession Factory for Artificial Mineral Waters” in Leipzig in 1861 at Zeitzer Strasse 35, Oscar Struve co-owner of his father’s factory in Leipzig. It was also at about this time that he became became a Dr. phil. He himself lived in the “mineral water establishment”, which had its company headquarters on the ground floor. In 1864 Oscar Struve received the citizenship of Leipzig.

From 1886 Oscar Struve was the sole owner of the company “Dr. Struve’s, Royal Saxon conc. Mineralwasser-Anstalt ” in the Leipzig, and from this point located on Zeitzer Strasse 28. After his death, his wife Dorothea Augusta Struve became the owner of the mineral water factory.

Below Oscar’s sister Louise Adelgunde Struve (1841 – 1921) who married Carl Theordor Melchers (1839 – 1923) in 1864. They had a daughter Magdalene who married Gustav Pauli.