Gustav Karl Johann Christian von Struve was born on 11 October 1805 in Munich, Bavaria and died on 21 August 1870 in Vienna, Austria-Hungary. He was the son of Johann Christoph Gustav and Friedrike Sibille (Von Hochstetter) Struve. He was a surgeon, politician, lawyer, publicist, and a revolutionary during the revolution of 1848-1849 in Baden, Germany. He also spent over a decade in the United States and was active there as a reformer. He is referred to most often as just Gustav Struve.

Because so much has been written about Gustav’s political life, the reader of this page is referred to various other sites such as: Wikepedia, The Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions, Deutsche Biographie, etc. His vegetrianism has been well summarised HERE.

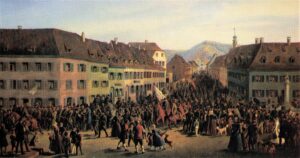

On this page we will focus on his bibliographic output, his family life, and his time in America where his daughters were born and his wife died. We will also gather a number of images depicting Gustav as a leader of the Baden revolution, but we will not go into much detail of his political activities.

His marriage took place at the Evangelisch, Mannheim, Baden. The bride was Elise Ferdinandine Amalie Duesar and it took place on 16th November 1845. His wife’s name varies considerably. One version is – Amélie Disar.

After his failed attempt at revolution, Gustav and his wife set off first for England and then to America in 1852. They stayed long enough in England to be noted on the 1851 census as ‘visitors’ to a household headed by Mr. Edwin Parker, a cow keeper, living at No. 2 Pratt Terrace in St Pancras, London (last two entries).

In America he first settled in Philadelphia and then moved to New York. He edited German-language newspapers, wrote several novels and started to write a huge World History (from a very left-wing perspective). Like many other German-Americans, he supported Abraham Lincoln and fought on the Unionist side in the Civil War. He always felt more European than American, however, and in 1863 he took advantage of the general amnesty offered to former revolutionaries and returned home to Germany.

In 1860 Gustav managed to persuade his younger brother Heinrich to return to Germany and try to sell his book World History. Heinrich recounts the experience as follows:

Then Gustav suggested that I should become a traveling salesman for his “World History” in Germany. He had a conference with several men who had convinced him that his book would become a best seller, and there was one man among them who informed Gustav that he would finance the printing of the book and also take the risk. So I agreed with Gustav’s suggestion. I did not think of the fact that with my decision I lost the protection of the high persons in Germany. But I could no longer be without work, so I left New York for Hamburg.

Gustav’s “World History” was a failure. The bookshops were not interested since the book had a republican tendency; and people who had this tendency were not rich enough to buy the book. My poor brother had worked for thirty years, and now his book would never be read. Gustav had worked in the libraries in Germany and England, and the book was to be the crowning achievement of his life. Those gentlemen in New York who had told Gustav that his book would be a big success had been wrong. I had traveled to Hamburg, Leipzig, Jena, and even Switzerland, and could not find any customers in one of these places I had to give up the idea of selling Gustav’s book.

Below, Gustav seated at a table with his wife Amalie standing over him plotting revolution.

Gustav and Amalie had three daughters: The first Amalie died in infancy in 1859. The second was Damajanti Frieda Struve who was born on 16 November 1860 at Staten Island. On 15 November, 1883, she filed a claim to receive her father’s army pension:

Frieda Damajanti Struve appears on the 1881 census for England as a “Foreign Governess” residing in the household of Margaret Priest at Landsdowne House, at Clacton 0n Sea.

Frieda Damajanti appears listed as living in Leipzig at Lindenau, Karl HeineStr. 66 II. Occupation: Vermieterin (landlady). She died in 1937 at Gernsbach, Rastatt, Baden-Württemberg.

A second daughter, Amalie, was born in 1862 at Stapleton, Staten Island, New York. Her mother Amalie died while giving birth to her. Later on, as an adult, she returned to Europe where she was twice married. First to Johann Lumann who was an engineer born in Moscow, He died before 1900. Amalie then married K Salzman at Riga, Latvia, where she died in 1918.

The enlistment date for Gustav’s joining the Union Army was 23 April 1861 at New York City, New York, with the rank of 2nd Lieut in the 8th Infantry. Two months later he was raised to the rank of 1st Lieut

On 21 July 1860 Gustav applied for US naturalization:

Below, Gustav’s application for a US Passport:

On 14 August 1867 in Manhattan, New York, Gustav married Catharine Kobiz Kentner a twenty five year old widow whose maiden name was Kobiz. She had been born in Hamburg, the daughter of Jacob Kobiz and his wife Philippina Herold.

In ‘Heroes of the Exile’ Karl Marx took a couple of cheap shots at Gustav as follows:

Gustav Struve is one of the more important figures of the emigration. At the very first glimpse of his leathery appearance, his protuberant eyes with their sly, stupid expression, the matt gleam on his bald pate and his half Slav, half Kalmuck [a western mongol people] features one cannot doubt that one is in the presence of an unusual man. And this first impression is confirmed by his low, guttural voice, his oily manner of speaking and the air of solemn gravity he imparts to his gestures. To be just it must be said that faced with the greatly increased difficulties of distinguishing oneself these days, our Gustav at least made the effort to attract attention by using his diverse talents — he is part prophet, part speculator, part bunion healer — centering his activities on all kinds of peripheral matters and making propaganda for the strangest assortment of causes. For example, he was born a Russian but suddenly took it into his head to enthuse about the cause of German freedom after he had been employed in a minor capacity in the Russian embassy to the Federal Diet and had written a little pamphlet in defence of the Diet. Regarding his own skull as normal he suddenly developed an interest in phrenology and from then on he refused to trust anyone whose skull he had not yet felt and examined. He also gave up eating meat and preached the gospel of strict vegetarianism; he was, moreover, a weather-prophet, he inveighed against tobacco and was prominent in the interest of German Catholicism and water-cures. In harmony with his thoroughgoing hatred of scientific knowledge it was natural that he should be in favour of free universities in which the four faculties would be replaced by the study of phrenology, physiognomy, chiromancy and necromancy. It was also quite in character for him to insist that he must become a great writer simply because his mode of writing was the antithesis of everything that could be held to be stylistically acceptable.

In the early Forties Gustav had already invented the Deutscher Zuschauer, a little paper that he published in Mannheim, that he patented and that pursued him everywhere as an idée fixe. He also made the discovery at around this time that Rotteck’s History of the World and the Rotteck-Welcker Lexicon of Politics, the two works that had been his Old and New Testaments, were out of date and in need of a new democratic edition. This revision Gustav undertook without delay and published an extract from it in advance under the title The Basic Elements of Political Science. He argued that the revision had become “an undeniable necessity since 1848 as the late-lamented Rotteck had not experienced the events of recent years”.

In the meantime there broke out in Baden in quick succession the three “popular uprisings” that Gustav has placed in the very centre of the whole modern course of world history. Driven into exile by the very first of these revolts (Hacker’s) and occupied with the task of publishing the Deutscher Zuschauer once again, this time from Basel, he was then dealt a hard blow by fate when the Mannheim publisher continued to print the Deutscher Zuschauer under a different editor. The battle between the true and the false Deutscher Zuschauer was so bitterly fought that neither paper survived. To compensate for this Gustav devised a constitution for the German Federal Republic in which Germany was to be divided into 24 republics, each with a president and two chambers; he appended a neat map on which the whole proposal could be clearly seen. In September 1848 the second insurrection began in which our Gustav acted as both Caesar and Socrates. He used the time granted him on German soil to issue serious warnings to the Black Forest Peasantry about the deleterious effects of smoking tobacco. In Lörrach he published his Moniteur with the title of Government Organ — German Free State — Freedom, Prosperity, Education. This publication contained inter alia the following decree:

“Article 1. The extra tax of 10 per cent on goods imported from Switzerland is hereby abolished;

Article 2. Christian Müller, the Customs Officer is to be given the task of implementing this measure.”

He was accompanied in all his trials by his faithful Amalia who subsequently published a romantic account of them. She was also active in administering the oath to captured gendarmes, for it was her custom to fasten a red band around the arm of every one who swore allegiance to the German Free State and to give him a big kiss. Unfortunately Gustav and Amalia were taken prisoner and languished in gaol where the imperturbable Gustav at once resumed his republican translation of Rotteck’s History of the World until he was liberated by the outbreak of the third insurrection.

Gustav now became a member of a real provisional government and the mania for provisional governments was now added to his other idées fixes. As President of the War Council he hastened to introduce as much muddle as possible into his department and to recommend the “traitor” Mayerhofer for the post of Minister for War (vice Goegg, Retrospect, Paris 1850). Later he vainly aspired to the post of Foreign Minister and to have 60,000 Florins placed at his disposal. Mr. Brentano soon relieved Gustav of the burdens of government and Gustav now entered the “Club of Resolute Progress” from which he became leader of the opposition. He delighted above all in opposing the very measures of Brentano which he had hitherto supported. Even though the Club too was disbanded and Gustav had to flee to the Palatinate this disaster had its positive side for it enabled him to issue one further number of the inevitable Deutscher Zuschauer in Neustadt an der Haardt — this compensated Gustav for much undeserved suffering.

A further satisfaction was that he was successful in a by-election in some remote corner of the uplands and was nominated member of the Baden Constituent Assembly which meant that he could now return in an official capacity. In this Assembly Gustav only distinguished himself by the following three proposals that he put forward in Freiburg: (1) On June 28th: everyone who enters into dealings with the enemy should be declared a traitor. (2) On June 30th: a new provisional government should be formed in which Struve would have a seat and a vote. (3) On the same day that the previous motion was defeated he proposed that as the defeat at Rastatt had rendered all resistance futile the uplands should be spared the terrors of war and that therefore all officials and soldiers should receive ten days’ wages and members of the Assembly should receive ten days’ expenses together with travelling costs after which they should all repair to Switzerland to the accompaniment of trumpets and drums.

When this proposal too was rejected Gustav set out for Switzerland on his own and having been driven from thence by James Fazy’s stick he retreated to London where he at once came to the fore with yet another discovery, namely the Six scourges of mankind. These six scourges were: the princes, the nobles, the priests, the bureaucracy, the standing army, mammon and bedbugs. The spirit in which Gustav interpreted the lamented Rotteck can be gauged from the further discovery that mammon was the invention of Louis Philippe. Gustav preached the gospel of the six scourges in the Deutsche Londoner Zeitung [German London News] which belonged to the ex-Duke of Brunswick. He was amply rewarded for this activity and in return he gratefully bowed to the ducal censorship. So much for Gustav’s relations with the first scourge, the princes. As for his relationship with the nobles, the second scourge, our moral and religious republican had visiting cards printed on which he figured as “Baron von Struve”.

If his relations with the remaining scourges were less amicable this cannot be his fault. Gustav then made use of his leisure time in London to devise a republican calendar in which the saints were replaced by right-minded men and the names “Gustav” and “Amelia” were particularly prominent. The months were designated by German equivalents of those in the calendar of the French Republic and there were a number of other commonplaces for the common good. For the rest, the remaining idées fixes made their appearance again in London: Gustav made haste to revive the Deutscher Zuschauer and the Club of Resolute Progress and to form a provisional government. On all these matters he found himself of one mind with Schramm and in this way the circular came into being