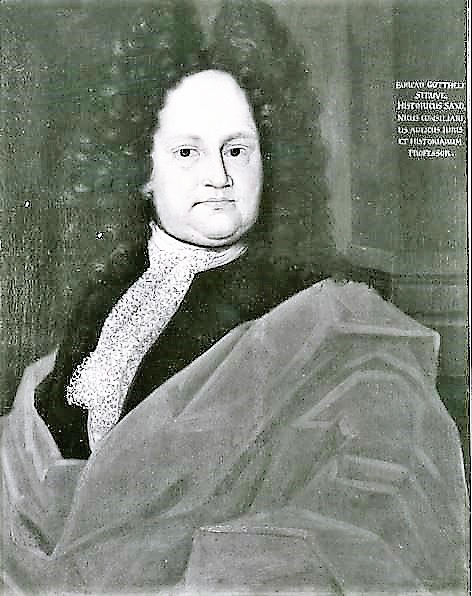

BURKHARD / BURCHARD GOTTHELF STRUVE was the third son by the second marriage of Georg Adam Struve to Susanna Berlich. He was born at Weimar on the 26th May 1671. His siblings included Margaretha Barbara and Friedrich Gottlieb Struve.

He was brought by his parents to Jena, when his father transferred his residence to that university, on receiving the appointment of Ordinarius of the Law College there, in 1674. Great pains were taken with his education by his parents; and in later life Struve often acknowledged his obligations to Johann Friedrich Durre, who had the charge of his elementary education.

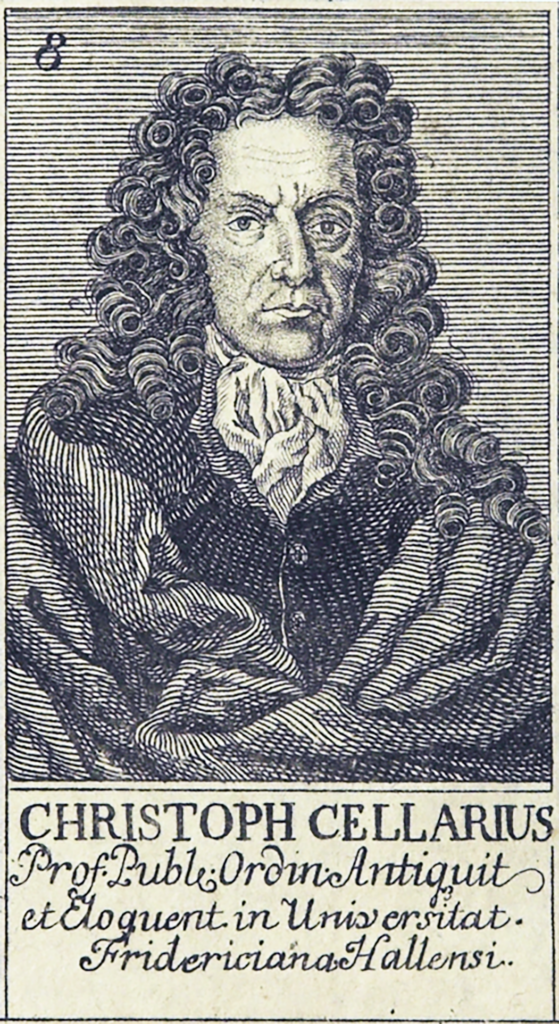

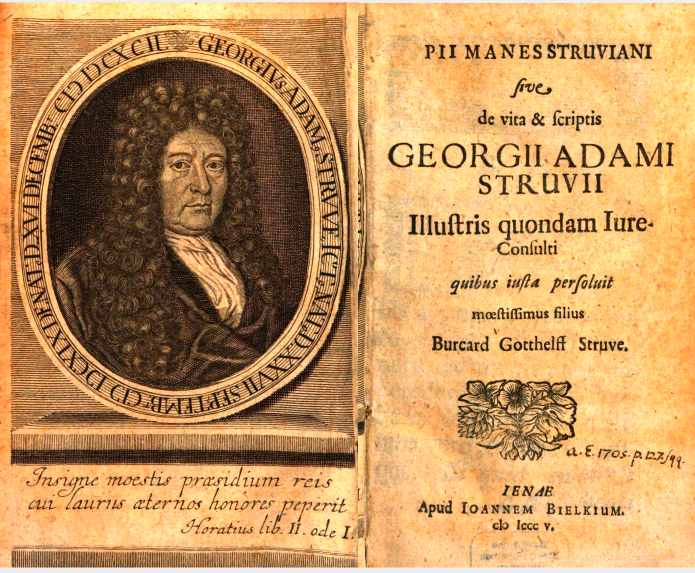

An incident mentioned in the Memoir of his father, which he published in 1705, almost leaves the impression that the old gentleman treated him in boyhood like a favourite plaything. The last time Georg Adam Struve presided at the creation of a number of doctors of law, in 1680, he commanded Burkhard / Burchard, then a boy of nine years only, to make his remarks, and put questions with the rest of the assembly. Not long after this event the boy was sent to the gymnasium at Zeitz, and was confided to the care of Christopher Cellarius rector of the institution. Young Burkhard made himself so useful to his preceptor, both in his private study and in the public library, that he gained his confidence sufficiently to be employed as an assistant upon the corrected and enlarged edition of his ‘Lexicon,’ which he had undertaken to publish.

Burkhard Gotthelf Struve, having attained his seventeenth year, returned to Jena for the purpose of commencing his university studies, in 1688.

Burkhard attended the lectures by Johann Hartung and Peter Muller on Roman law, but he seems have been a more assiduous frequenter of the literary classes of Jacob Muller, Andreas Schmidt, and especially of Georg Schubart, then rector of the university, under whose presidency he held, in 1689, a public disputation upon some theses appended to his dissertation De Ludis Equestribus.

Not long after he disputed in the juridical faculty on the legal doctrines ‘De Auro Fiuviatili;’ and on both occasions he is said to have impressed his interlocutors with admiration of his precocious talents. While thus engaged, he did not neglect pursuits more consonant to the tastes of his age, country, and academic associates. He learned dancing, and was for a time a frequent attendant in the fencing-school. Tiring however of these pursuits, he devoted himself with ardour, in his leisure hours, to the study of the French language. In the Memoir of his father, already alluded to, he mentions that about this time he was employed by his father in a collation of his Latin treatise ‘Jurisprudentia Romano-Germanica Forensis,’ with his work on the same subject in German, to show that the one was not a mere translation of the other, but a different work. The statement which Burkhard drew up on this occasion was meant to be inserted in the pleadings of the publisher of the German work, against whom the publisher of the other had brought an action; but it was published, at a later period, by the bookseller, as a preface to a new edition, without the compiler’s knowledge or consent. An exercise of this kind, and the repetitions under his father, were well calculated to impress the leading doctrines of the law upon his memory.

Towards the close of the same year in which he maintained his first public disputations, Burkhard Gotthelf Struve repaired to the University of Helmstedt, for the purpose of studying history under Heinrich Meibom, and civil law under Georg Eugelbrecht. After a year’s residence at Helmstedt he went to Frankfurt-on-the-Oder, in order to profit by the instructions of Samuel Stryk and Peter Schulz. During his time at Frankfurt he engaged in a controversy which led him to appear for the first time in print.

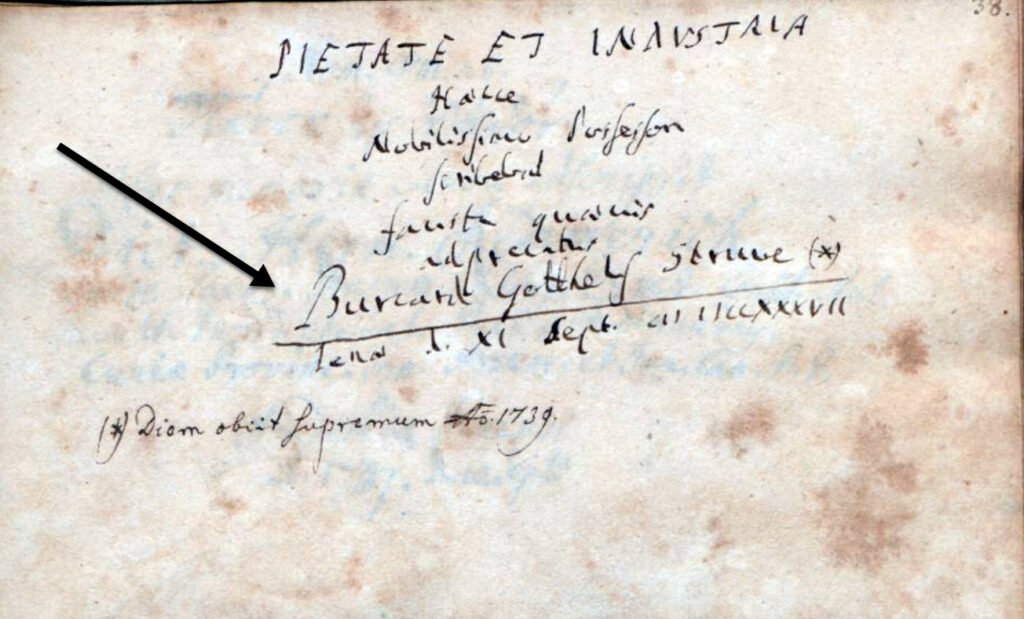

In 1691 Struve returned to Jena, and was soon after sent to Halle by his father, with a view to his attending the sittings of the supreme court there, in order that he might make himself master of the forms of process.

The dry details of legal practice were repulsive to a mind early accustomed to the self-indulgent habits of the abstract student, and to the applause attendant upon skill in mere literary controversy. Instead of frequenting the court, he directed himself almost exclusively to the theory and antiquities of public and feudal law. In such a frame of mind he lent a willing ear to the inducements held out by his elder half brother, Johann Wilhelm, to make a tour to Belgium, and afterwards join him at Darmstadt, where he was established as a lawyer.

He in consequence visited in succession Gotha, the Hague, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and Leyden, and was everywhere, on account of his father’s reputation, kindly received. He afterwards confessed that his thoughts during this journey were rather distracted by the gaiety and splendour of the towns he visited, than earnestly bent upon extending his knowledge; nor was this very unpardonable in one who had only completed his twentieth year. He did however derive some benefit from the conversation of distinguished scholars in Utrecht and Leyden.

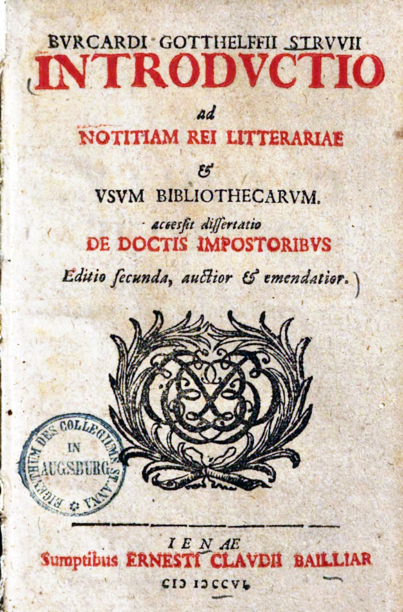

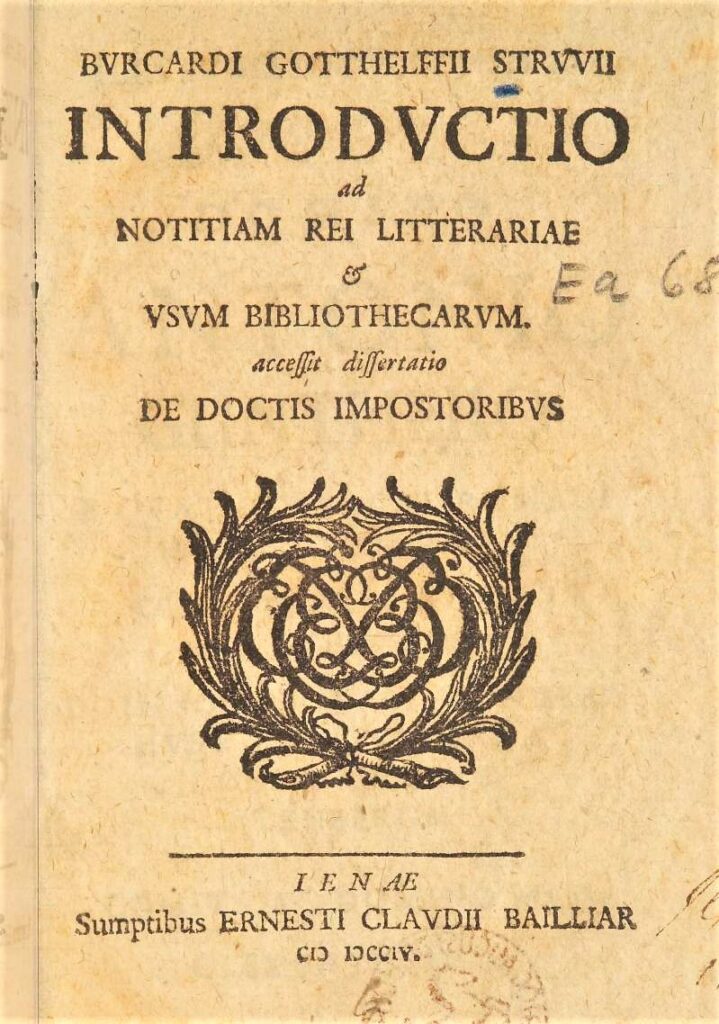

Burchard Gothelf was one of the earliest scholars to engage on the topic of forgeries / fakeries with his book De Doctis Impostoribus which included an analysis of what happened when Pope Gregory IX invented a book that “proved” Moses, Jesus, and Mohammed were charlatans and then pinned the authorship on his arch enemy Frederick II, the Holy Roman Emperor. Unfortunately for Gregory the book did little harm to Frederick as it was seen by most for what it was.

In 1701 his half-brother Johann Wilhelm Struve published in D. Nicolai Vigelii, weyl. vornehmen JCti. zu Marpurg, Gerichts-Büchlein : samt dem Zusatz von ungewissen Rechten, wie auch mit einem Gespräche eines Oratorn und Juristen über dieses Büchlein …

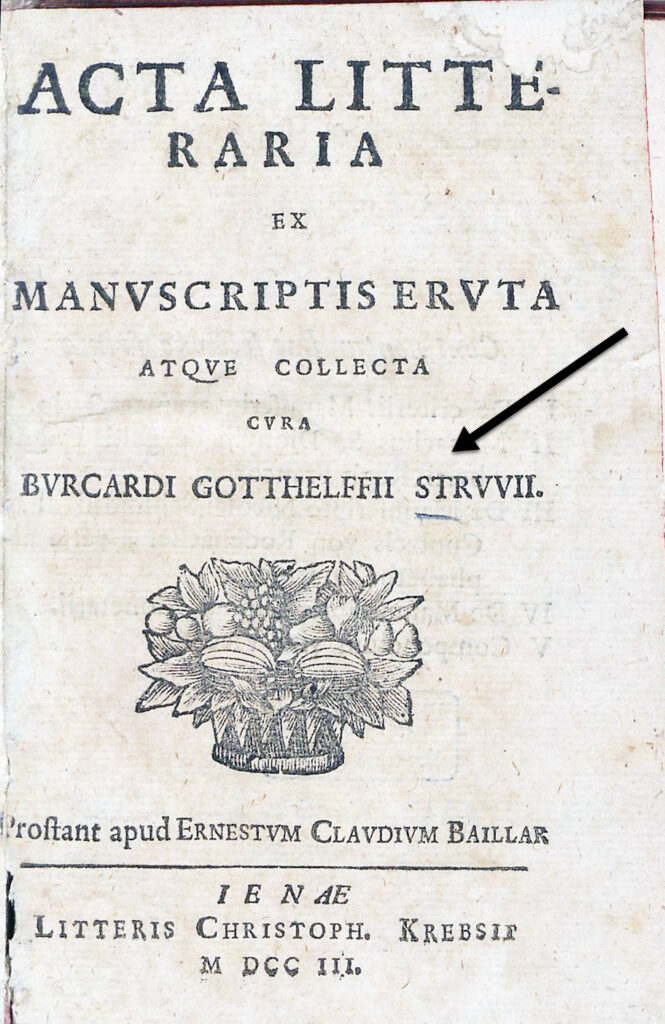

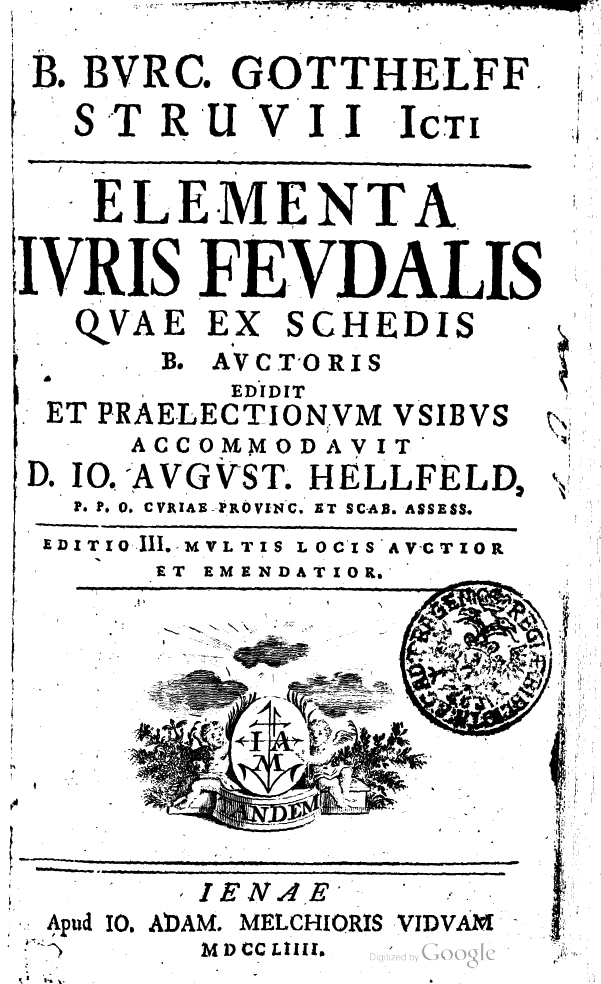

At the request of his brother, Johann Wilhelm Struve, he went to Frankfurt to take charge of some business for the transaction of which he required a confidential agent in that town. It was the time of the fair, and the novelty and bustle of the scene left a lasting impression upon Struve’s mind. The affairs that required his presence there being arranged, he returned to the Hague, and, the first distraction of travelling having worn off, settled to study. The favourite pursuits of the Dutch literati extended his field of inquiry. On the one hand, the Hague being then a centre of an active diplomacy, his investigations regarding public law were enabled to assume a more practical and real character. Below, just some of the many many books published by Struve:

The literary pursuits too of his new associates had more of the tone of society than those which prevailed in the German universities. On the other hand, the museums of Holland, and especially the collections of coins and other antiquities, attracted him to inquiries for which his investigations into the antiquities of feudal law had in some measure prepared him. During his residence at the Hague he was indefatigable in his visits to all the museums and libraries, and in his study of the periodical literature, which opened in a manner a new world to him. Ho made for himself a considerable collection of coins and antiquities. While thus engaged, and projecting a tour through Spain and Great Britain, he was seized with a violent illness, which interrupted his pursuits.

On his recovery he rejoined his brother and was employed by him a number of times to conduct various cases for him in the courts of Darmstadt, Stuttgart, and Cassel. He was induced about this time by the fair promises of a Livonian nobleman to undertake a journey in his company to Sweden for the purpose of obtaining a more intimate acquaintance with the antiquities of Scandinavia. Struve with this view proceeded to Hamburg, where he was to be joined by his companion. The count not making his appearance however, he returned to his brother, and in the same year (1692) visited Wetzlar, for the purpose of obtaining, by attending the sittings of the imperial court, a more accurate knowledge of the practice of public law. While thus engaged, he was attacked by a more severe illness than the preceding; and some of the symptoms induced a suspicion that it was occasioned by poison. No sooner was he convalescent than he received intelligence of the death of his father and was obliged to leave Wetzlar in order to look after his share in the inheritance. During the period that elapsed between his quitting the University and his return to Jena, his mind, though stimulated to greater activity and with objects of greater reality and importance than had previously engaged his attention, had been dissipated and distracted with their multiplicity. To the end of his life he occasionally expressed regret that he had not, in compliance with the request of his father, remained at Jena, to digest under his direction his collections for a commentary on the law of marriage, an occupation that must have contributed to give him more precision and more command over his thoughts.

On his return to Jena, Struve found one of his brothers (Georg Gottlob), who tried his luck at various courts and also in Holland as an alchemist, engaged in pursuit of the philosopher’s stone. This brother was of a facile disposition, as is apparent from an anecdote he relates in the Life of his father, of his incurring a rebuke by undertaking to solicit privately for a person whose conduct was under judicial investigation. This easiness of temper at first led him to join in his brother’s experiments, but the frenzy seized him in turn, and he was soon as zealous an adept as the other.

As might have been anticipated, the search after the secret of making wealth ended in beggaring both. The brother was only saved from jail by Struve selling the collection of curiosities he had gathered in Holland, and even a part of his wardrobe. The intoxication of his dreams of wealth was succeeded by a state of miserable depression that lasted for two years. He secluded himself away from society, and absorbed himself in the study of the Scriptures and the theological writings of Tauler and Arndt.

When he recovered his elasticity of mind, he found himself unable to encounter the expense of following the academic career that his father had steered him toward. Some time elapsed before any prospect of employment opened to him. In 1695 he published at Frankfurt-on-the-Main some remarks on Gothofredus (known among jurists as the Immo of Gothofredus) from a manuscript of his father’s (see above).

In 1696 he published a letter to his old teacher Christoph Cellarius: Epistola Ad Virum Clarissimum Christophorum Cellarium Eloquentiae in nova Fridericiana …

In 1697 he was appointed by the patrons of the University of Jena curator of the library. Upon receiving this appointment, he opened private classes, giving instruction, according as his pupils desired, in physics, the elements of the Greek language, Roman antiquities, or history. The number of young men who attended him excited the envy of the established teachers and drew down upon him the active enmity of Georg Schubart (1650-1701). It was found necessary to provide himself with a legitimation as teacher; and for this end he, in the year 1702, took the degree of Doctor of Law and Philosophy at Halle.

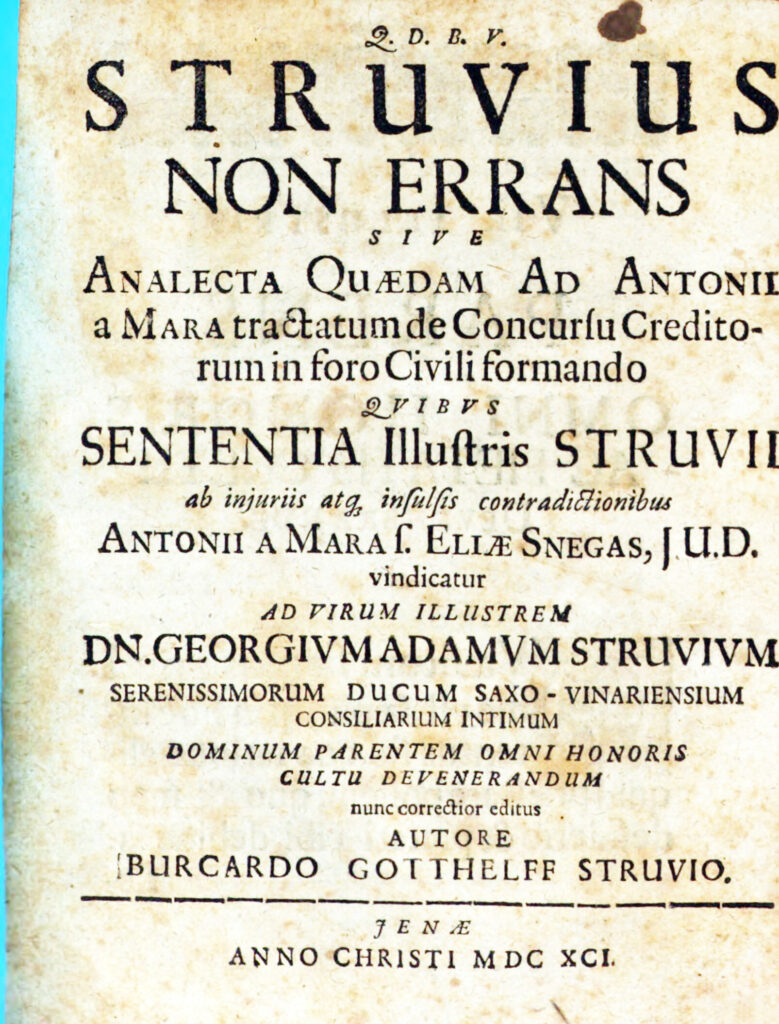

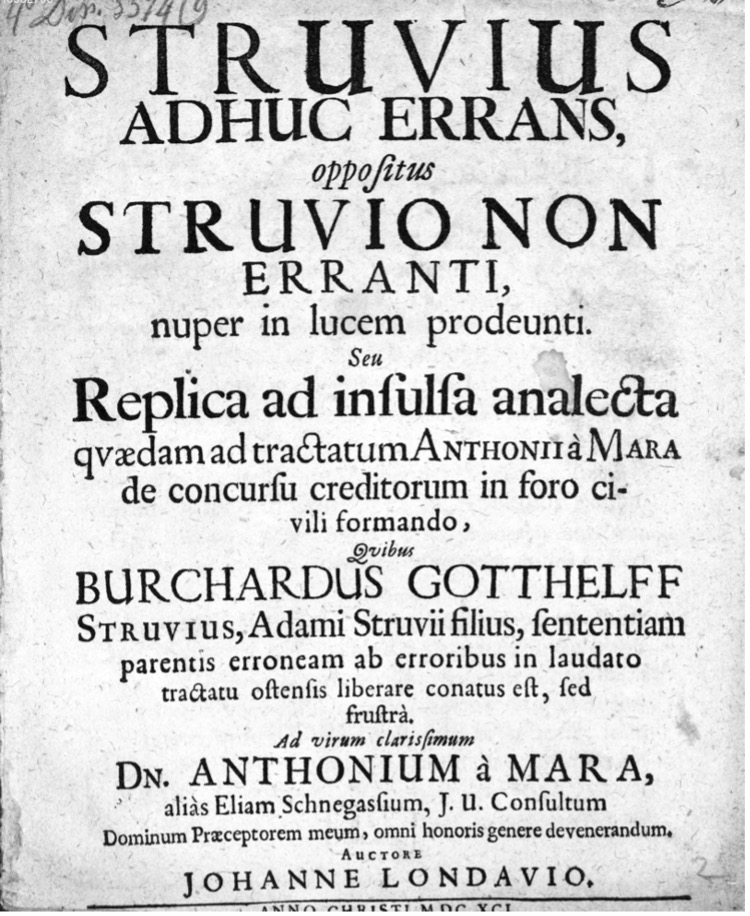

In 1689 and again in 1697 Anthony Mara (Elias Schneegass) opened up a series of attacks on Georg Adam Struve’s legal theories as laid down in his ‘Institutes of Forensic Law’ regarding the classification of creditors and the right of property in dowry in Tactatus De Concursu Creditorum In Foro Civili Formando …. In response, Burchard Gotthelf published Struvius non errans, sive analecta quaedam ad Antonii a Mara tractatum … in which he asserted the correctness of his father’s views. However, in response to this Mara challenged Burchard Gotthelf’s defence of his father in Struvius Adhuc Errans, oppositus Struvio Non Erranti, nuper in lucem prodeunti … However, Burchard Gotthelf was persuaded not to respond to this which, to judge by the warmth with which he spoke of the controversy at a much riper age, must have been rather bitter.

As soon as he obtained his degree, he took measures for having himself enrolled as Doctor of Law at Jena, and his subsequent career was one of uninterrupted success. On the death of Schubart he was appointed to the chair of history, and he commenced the discharge of its duties in 1704 by publishing a programme De Vitiis Historicorum and delivering a public oration De Meritis Germauorum.

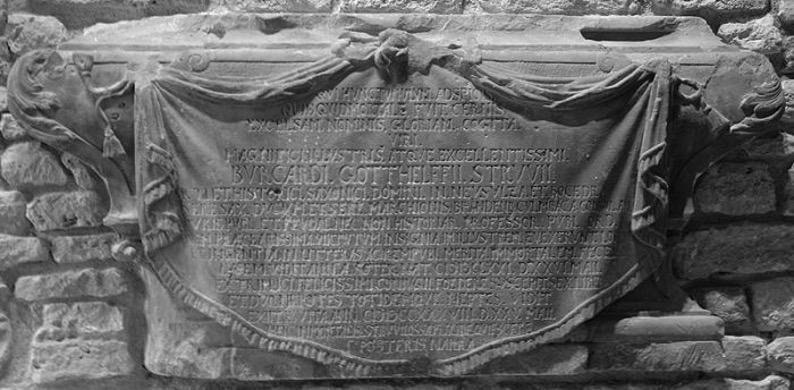

His fame as a public teacher attracted many of the young nobility from all parts of Germany, and among others Prince Ernest Augustus, afterwards duke of Weimar. Having received in 1712 an invitation to the University of Kiel, he was induced to decline it by the patrons of Jena conferring upon him the office of historiographer to the university, the rank of counsellor, and the appointment of extraordinary professor of law. He was promised the succession to the ordinary professorship of feudal law, which he actually obtained a few years later. In 1717 he was appointed a privy councillor by the reigning prince of Baireuth, and in 1730 he received the same compliment from the Saxon court. He repeatedly filled the office of dean in the Philosophical faculty and was thrice chosen rector of the university. He died on 24 May 1738, having nearly completed his sixty-seventh year.

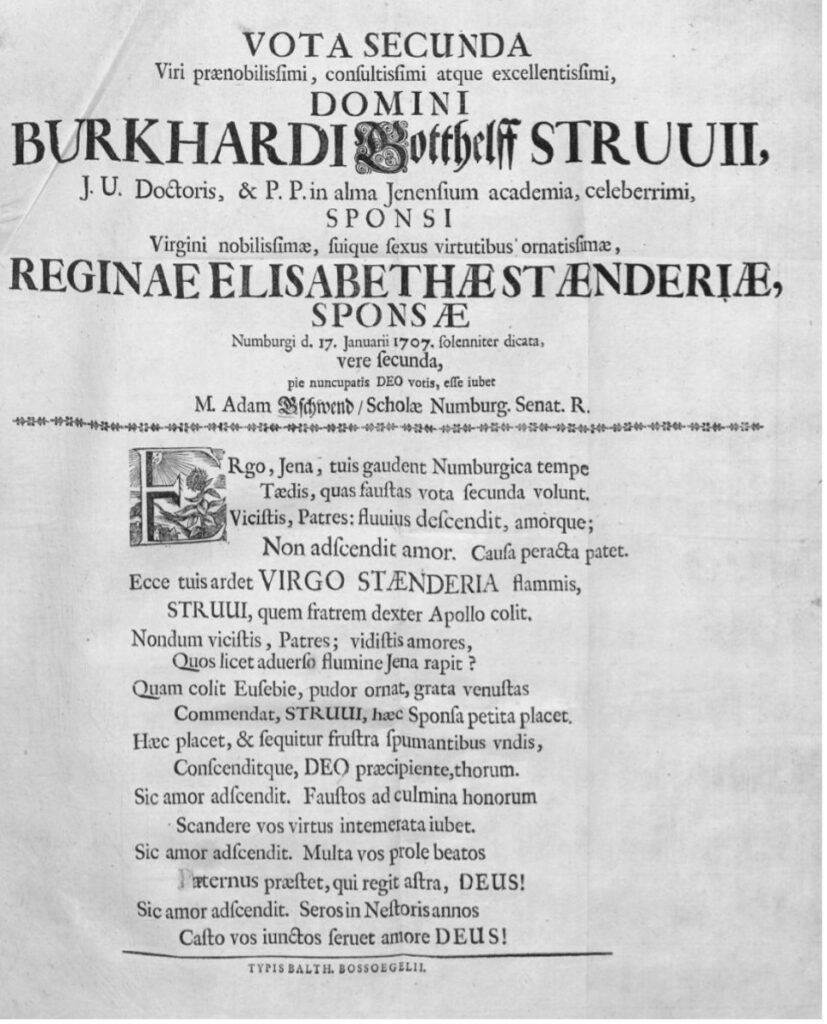

Struve was thrice married, he was united to his first wife, Anua Elizabetha Bertram, daughter of an assessor in the court attached to the salt-works of Halle, in 1702, who died in 1706, leaving him three daughters. He married in 1707 his second wife, Regina Elisabetha Stander (died 1722), daughter of Joachim and Blandina Regina Ständer town-clerk of Naumburg on the Sala.

On their marriage a poem was published: Vota Secunda Viri prænobilissimi, consultissimi atque excellentissimi, Domini Burkhardi Gotthelff Struuii, J. U. Doctoris, & P. P. in alma Jenensium academia, celeberrimi, Sponsi Virgini nobilissimæ … Reginae Elisabethæ Stænderiæ, Sponsæ Numburgi d. 17. Januarii 1707. …

She left no surviving children. On her death, in 1720 a funeral sermon was published Programma in Exsequiis Maximarum Virtutum ac Laudum Matronae Reginae Elisabethae Struviae [not yet digitized].

In 1724 he married Sophia Maria Hanses, widow of Ernst Friedrich Kettner (1671 – 1722), a clergyman in Quedlenburg, who brought him no children.

The published works of Burkhard Gotthelf Struve are very numerous. A complete list of them is given in the Acta Kruditorum of Leipzig, published in 1740.

In 1722 Burchard drew a watercolor illustration of Castle Tautenburg:

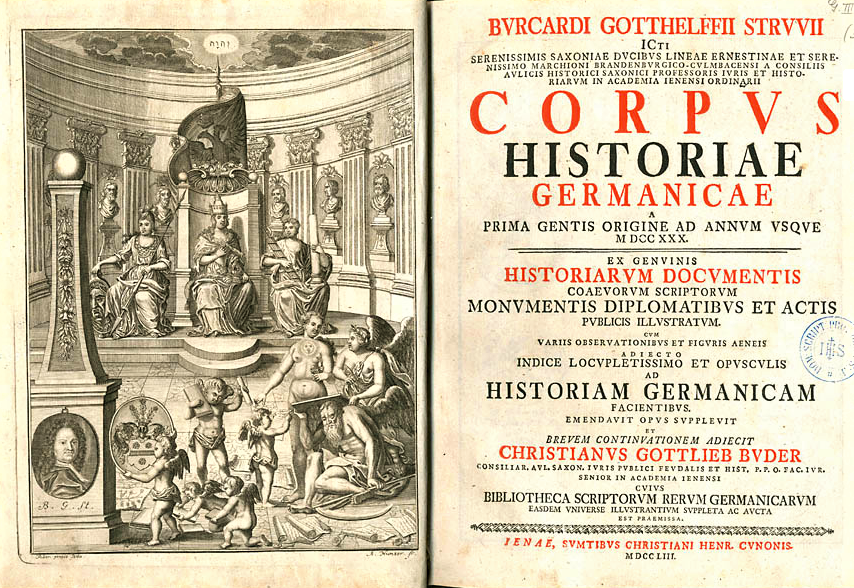

In 1730 he published: Bvrcardi Gotthelffii Struvii icti, … Corpvs historiæ Germanicæ : a prima gentis origine ad annvm vsqve M DCC XXX … which he dedicated to King George II of great Britain and Elector of Hanover.

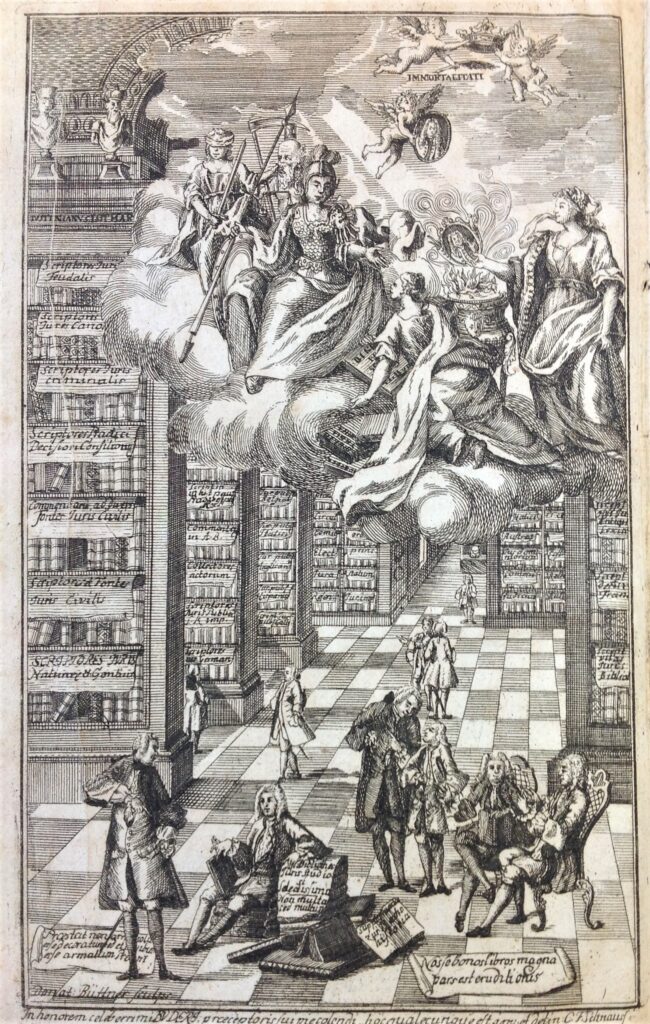

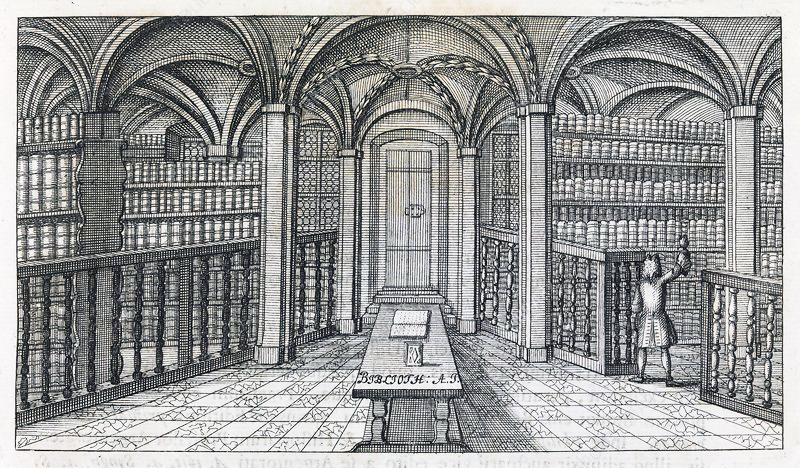

And which contains a rather nice illustration of a science library:

He was also responsible for launching some of Europe’s earliest serials Thesavrvs variae ervditionis ex scriptoribvs potissimvm and Bibliotheca Antiqua:

Much of the reputation of Burkhard Gotthelf Struve during his lifetime seems to have proceeded from his personal amiability, and from his usefulness as a general indexer. His style is heavy, and his thoughts are scarcely ever original or striking. His services to the literature of history and jurisprudence are great, but they are mainly the services of an able librarian and index-maker. To him perhaps rather than to Achenwall belongs the merit of having given a more systematic form to the statistical branch of education as taught in the universities of Germany — an important department of information, but too apt to spread out into trivial diffuseness.

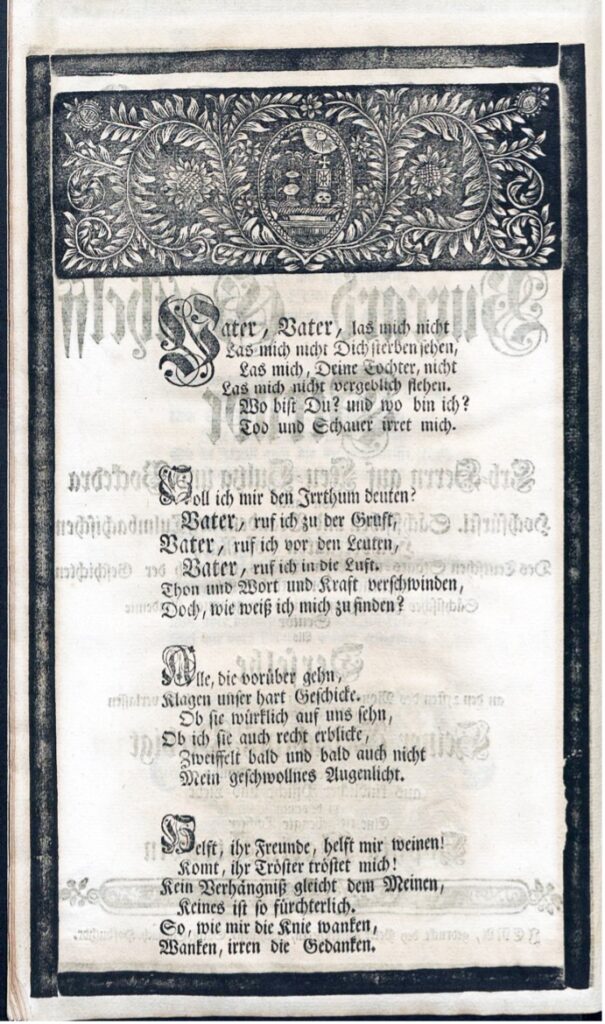

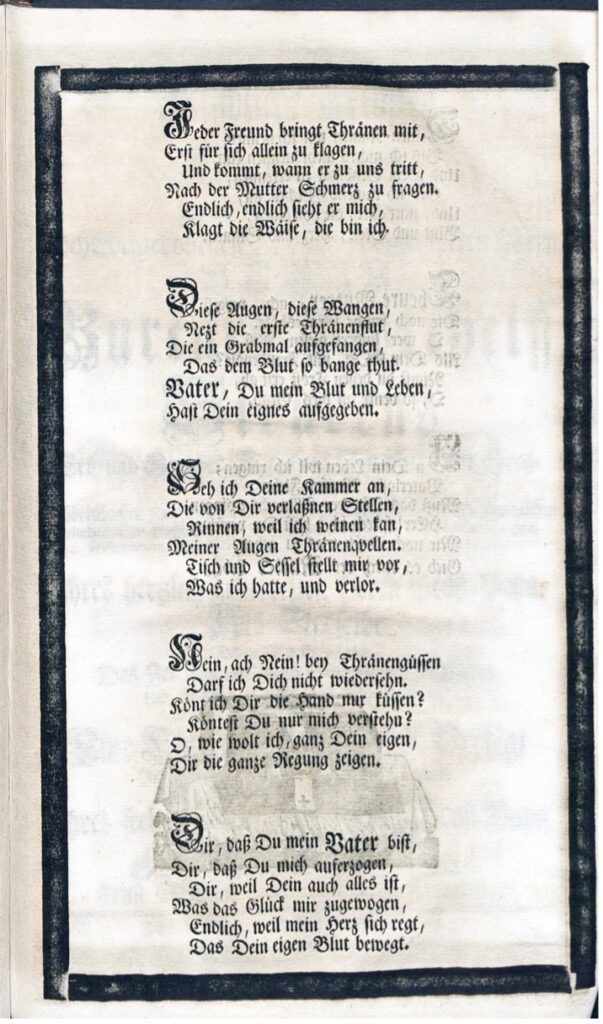

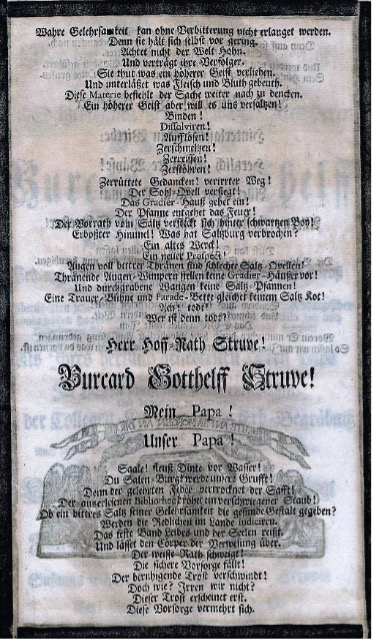

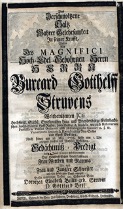

When he died, his wife and daughters published funeral verses in his honor such as: Bittre Thränen Welche Uber den höchst schmertzlichen Verlust Des Weyland Magnifici Hochedelgebohrnen Vest und Hochgelahrten Herrn Herrn Burcard Gotthelff Struven from which we learn that Burchard Gotthelf died “softly and blissfully” on May 25, 1738 and was buried on the 27th and that on June 22nd a “Christian memorial sermon was held in the town church in great melancholy”. One of the poems was written by his daughter Susanna Elisabetha.

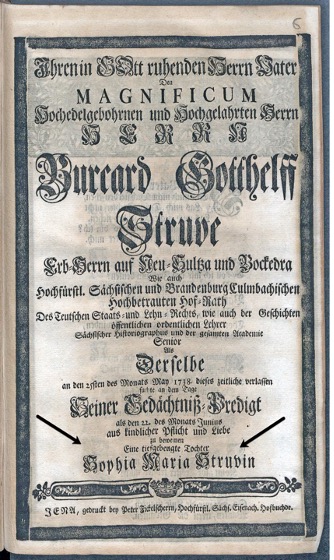

As noted, Burchard Gotthelf had three daughters: Dorothea Elisabeth who married Gottlieb Beil; Susanna Elisabeth who married Carl August Fabarius and Sophia Maria who does not appear to have married. She did however put her name to some funeral verses for her father under the title: Ihren in Gott ruhenden Herrn Vater Den Magnificum Hochedelgebohrnen und Hochgelahrten Herrn Herrn Burcard Gotthelff Struve … , which she concluded ‘ … out of weeping filial duty and love – a deeply bent daughter.

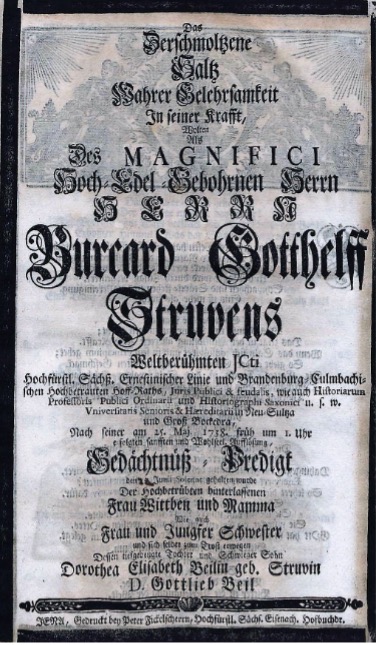

Below the funeral sermon on the death of Burchard Gotthelf Struve with mention of his daughter Dorothea Elisabeth Beil, the wife of Gottlieb Beil.

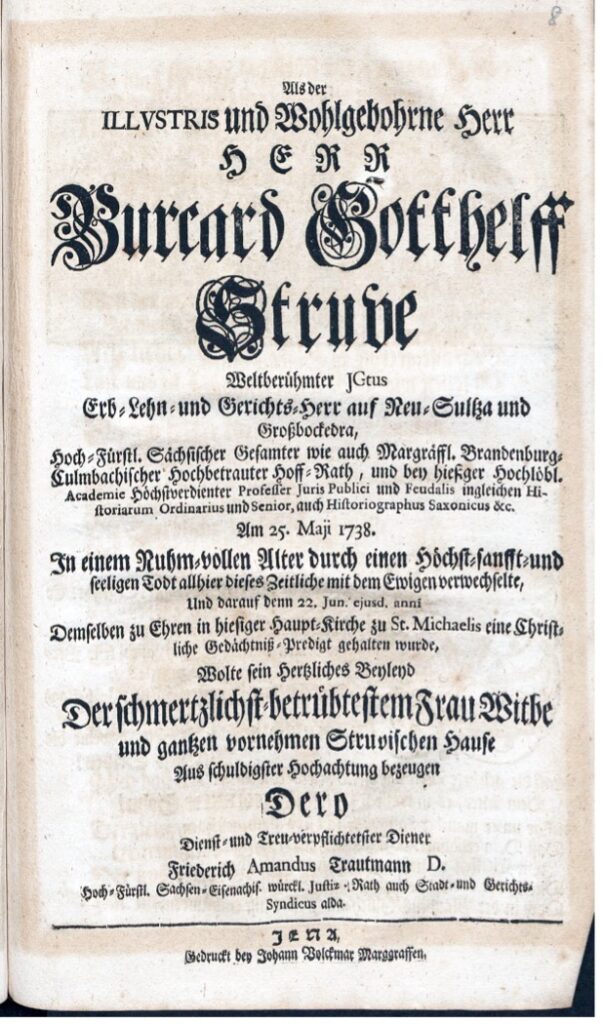

Another funeral book, much like the others, was titled: Als der Illvstris und Wohlgebohrne Herr Herr Burcard Gotthelff Struve Weltberühmter JGtus Erb- Lehn- und Gerichts-Herr auf Neu-Sultza und Großbockedra, Hoch-Fürstl. Sächsischer Gesamter wie auch Marggräffl.

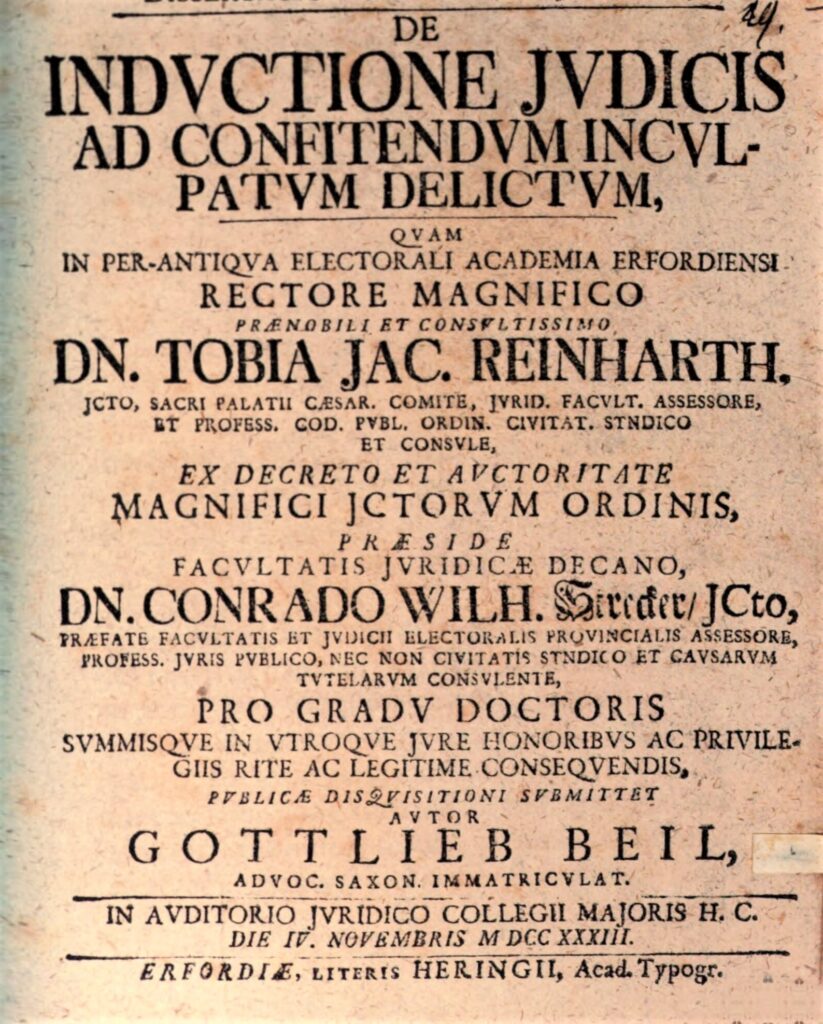

Below, Gottlieb Beil’s Diss. inaug. iur. de inductione iudicis ad confitendum inculpatum delictum … [1733]

Burchard Gotthelf’s other daughter – Susanna Elisabeth – married Carl August Fabarius. On the occasion, a wedding book was issued titled: Die Teutsche Gesellschaft in Jena stattete Bey der Verbindung Des Hochedlen, Vest und Hochgelahrten Herrn Herrn Carl August Febarius Der Rechten berühmten Doctoris und Hochgräflichen [Not yet digitized]. Which tells us that “the right famous doctor” Carl August Febarius is marrying “the highly noble born, high honored and virtuous maiden” Susanna Elisabeth Struve the daughter of the “high noble born and highly educated” Mr. Burchard Gotthelf Struve, etc.

And they had a son Ernst Christian Gotthelf August Fabarius and a daughter Sophia Judith Susanna Fabarius.

Sruve and his son in law Fabarius sometimes can be found writing together. For example: Als der Magnificvs Hoch-Edelgebohrne Herr, Herr Burcard Gotthelff Struve, Hochberühmter JCtvs … And, Dissertatio iuris publici de iure Landsassiatus in Thuringia …

When her father died, a funeral sermon was published with Susanna Elisabeth (Struve) Fabarius’s name on it: Bittre Thränen Welche Uber den höchst schmertzlichen Verlust Des Weyland Magnifici Hochedelgebohrnen Vest und Hochgelahrten Herrn Herrn Burcard Gotthelff Struvens …

The title tells us with “… bitter tears … about the most painful loss …” the daughter of Burchard Gotthelf Struve, Susanna Elisabeth, the wife of Carl August Fabarius, who mourns her father who died on May 25th, 1738 and that a Christian memorial sermon was held in the town churches in great melancholy.

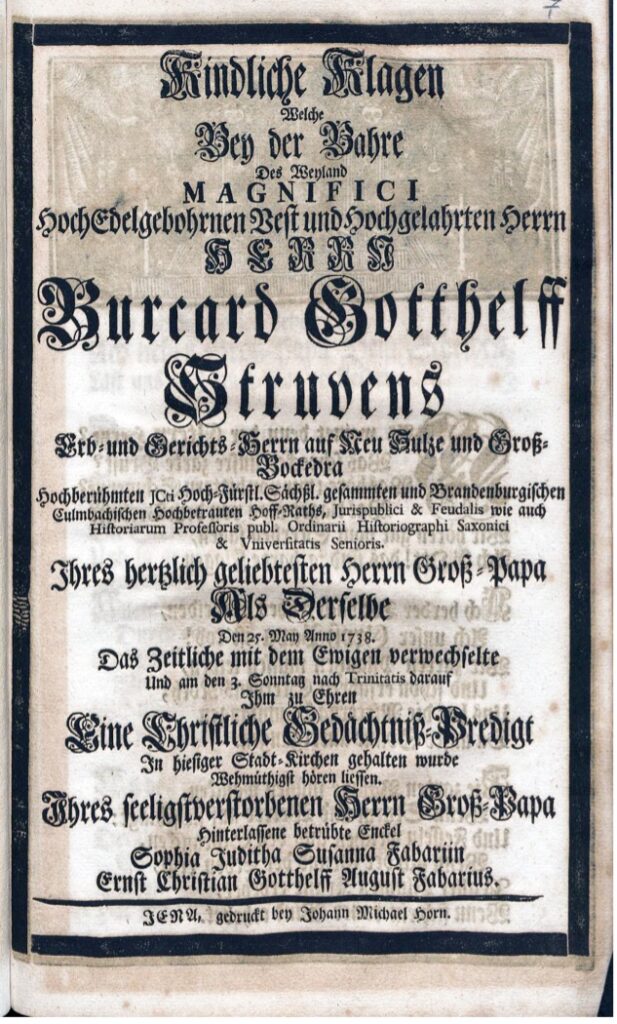

A granddaughter of Burchard Gotthelf Struve’s, Sophia Judith Susanna Fabarius, also published a sermon book for her grandfather: Kindliche Klagen Welche Bey der Bahre Des Weyland Magnifici Hochedel gebohrnen Vest und Hochgelahrten Herrn Herrn Burcard Gotthelff Struvens … dated May 25, 1738. This also included a contribution by Johann Michael Horn. And, on the 3rd Sunday after Trinity, a church memorial sermon was held in the local city church which was “wistfully heard”.

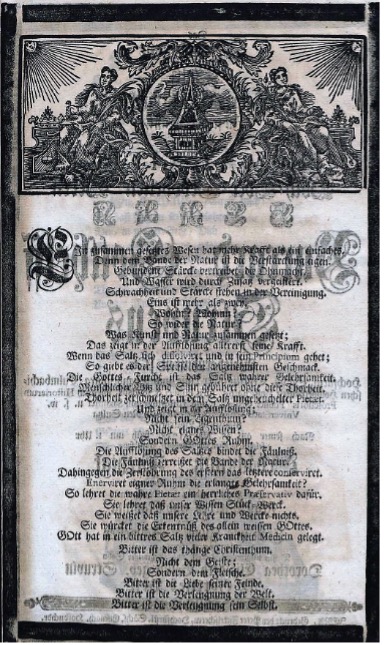

Das Verschmoltzene Saltz Wahrer Gelehrsamkeit In seiner Krafft, Wolten Als Des Magnifici Hoch-Edel-Gebohrnen Herrn Herrn Burcard Gotthelff Struvens Weltberühmten Jcti Hochfürstl. Sächß. Ernestinischer Linie und Brandenburg-Culmbachischen Hochbetrauten …